https://mountainjournal.org/growth-is-pushing-parts-of-jackson-hole-to-burst-at-its-seams

Teton County, Wyoming is one of many in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem struggling with conservation of wildlife, clean water and native plant communities in the face of burgeoning human occupation. Until recently we might be forgiven for considering this valley buffered from the kind of sprawl one sees around Bozeman, Montana on the north side of this bioregion because only 3 percent of this county is privately owned.

But public land is not guaranteed, as western lawmakers seek ever more clever and devious ways to usurp it. In the meanwhile, this region remains among the last strongholds in the Lower 48 for the wild world we claim to revere.

But for how long?

Federal land-use policies change with elections and are greatly influenced by the secretaries of agriculture and interior. We think acts of Congress like the Endangered Species, Wilderness, and Clean Water acts protect everything from our wildlands to the water we take for granted when we turn on the tap at home, but we see these landmark laws under constant attack. They have given the endangered a few decades of breathing room, but I find no assurances about the future.

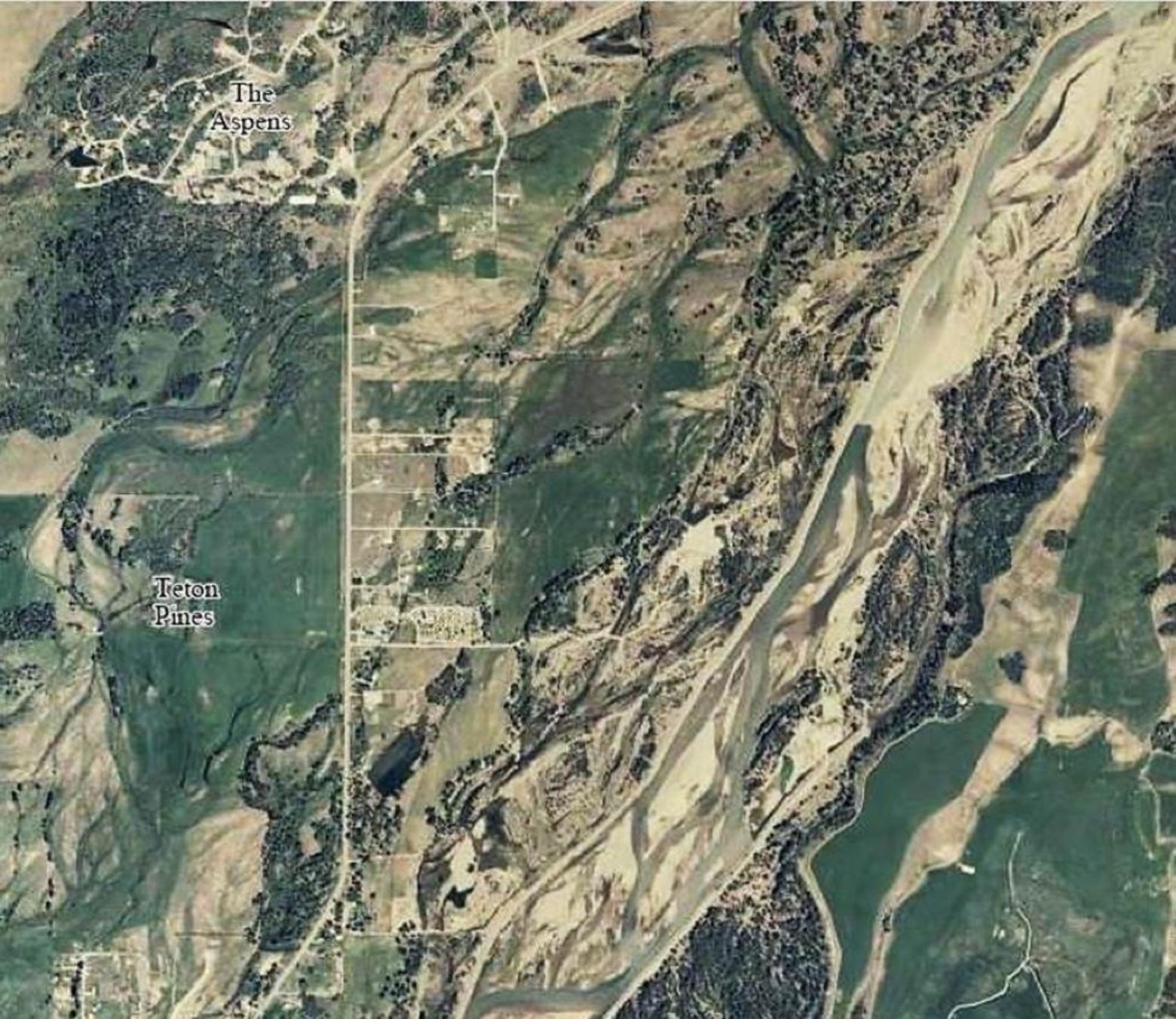

While public land is dominant in Teton County, it’s also true that the small percentage of private land is not to be discounted for its importance for wildlife habitat and movement across the landscape. A prime example is the Snake River between Grand Teton National Park and the south end of the valley. Beyond the river lies a riparian forest, important as a corridor for wildlife migration and nesting habitat for birds, from warblers to eagles.

When Jackson Hole was first settled, a 1905 survey platted the Snake’s “meander lands” as part of adjacent ranches. The Bureau of Land Management filed suit in 1966, claiming a flawed and fraudulent survey. The matter was finally decided in a 1983 legal ruling that determined nearly all the parcels in dispute should go to the adjacent landowners. Three and a half decades later, much of the private ranchland has been sold and subdivided for high-end housing.

Levees built after the 1927 Gros Ventre River flood continue to be improved and maintained, protecting private property that grows in value and density every year. The result is fragmentation of habitat and loss of the periodic flooding necessary to regenerate cottonwood forests. The levees focus river flow and concentrate its energy instead of allowing it to spread and slow in its historic floodplain, thus contributing to seasonal flooding and erosion downstream.

Teton County, like others in the region, regulates development through zoning and related regulations. The comprehensive county plan means to steer new development into established areas, leaving open space and rural landscapes intact.

You could say the plan has helped: in 2015 the county updated its Rural Zoning Regulations, eliminating the potential for an additional 2,300 dwelling units to be built in wildlife habitat and open space. But there was plenty of building prior to the dawn of this zoning scheme, and plenty of long-approved development rights that continue to be exercised. The result is that over half of the new development in the county is still taking place in rural areas.

Before 1978, you could subdivide just about anywhere in the valley. While the comprehensive plan slowed that trend the options to preserve critical wildlife habitat along the Snake River are fewer than they might have been once, as seen in the 1977 and 2017 photos of a section of the Snake River south of Grand Teton National Park.

Teton County’s stated mission is to “preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem in order to ensure a healthy environment, community, and economy for current and future generations.” The county admits that existing development patterns have been problematic, for anyone who can afford to wants to locate in one of the exclusive subdivisions in the county, removed from the noise and congestion of town. Who can blame them?

Wyoming’s population growth rate from 2010-2018 was around 2.5 percent; in Teton County saw 8.4 percent. If that sounds like a lot, consider Teton County, Idaho and Gallatin County, Montana, with growth rates of 14.5 and 25 percents in the same period (US Census data). And read Mountain Journal’s ongoing coverage about the implications of more people and the development footprint being exacted, including a report by Todd Wilkinson titled Unnatural Disaster: Will America’s Most Iconic Wild Ecosystem Be Lost To A Tidal Wave of People?

The growth and sprawl in our area would likely match that of others if not for the public land that comprises 97 percent of the county.

We must also consider the so-called effective population —the total number of people day-to-day, which includes visitors, seasonal workers, commuters from nearby towns, and part-time residents. This number is expressed in crowding of roadways, town, and trails.

Job growth is the main driver around here, as more hotels, restaurants and visitor services are added, all of which need employees, and not all of which offer housing. Nearly 60 percent of the local workforce lives outside the community. So people commute to work from satellite communities Star Valley, the Hoback, Teton Valley and elsewhere. More travel on the road creates predictable hazards for wildlife.

So what is being done to resolve the difficult conflict between our human desires for more of everything and a sincere desire to protect clean waterways, wildlife habitat, and the beauty that people come here and live here to experience?

A number of studies, for one thing, conducted by governmental entities such as the Teton County Conservation District and Wyoming Game and Fish. The statewide wildlife action plan lists threats to native wildlife that will sound familiar to many, all of them caused by human activity and occupation of the land. Riverine and wetland habitats face invasive species, incompatible agricultural practices, transportation developments, maintenance of existing infrastructure like dams, weirs and dikes.

The Snake River in Jackson Hole is one of the agency’s “priority” wetland complexes and is listed as having high vulnerability due to ongoing and future development.

Where does one find this kind of information, with its research and recommendations? You can look up the 2017 State Wildlife Action Plan, assuming you know it exists. It has supposedly been widely distributed for use by agencies and county governments but people I know who don’t work for Game and Fish have mostly never heard of it.

Another more recent example is a science-based report, State of Wildlife in Jackson Hole, commissioned and paid for by the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance. It speaks directly to concerns along the Snake River. The report was completed in early 2018, but like the wildlife action plan, few people seem to know about it—much less use it.

“I suppose in this age of information overload, all these reports sound like a lot to read and absorb. Maybe it’s not up to each of us to be familiar with every word in every document, but we can at least ask our elected officials and county planners if they are referring to them at all. We can keep reminding them that citizens care, and we can glean from such documents information that might be persuasive.”

The Jackson Hole News and Guide publishes an annual magazine called Headwaters: Conservation in Greater Yellowstone. Jackson economist and town council member Jonathan Schechter publishes the annual Mosaic: The State of the Tetons Ecosystem. The articles and commentary found in the 2018 editions of both magazines, along with the publications noted above, bear a remarkable similarity. We seem to know pretty well what the problems are and many experts are available to suggest ways to confront them.

I suppose in this age of information overload, all these reports sound like a lot to read and absorb. Maybe it’s not up to each of us to be familiar with every word in every document, but we can at least ask our elected officials and county planners if they are referring to them at all. We can keep reminding them that citizens care, and we can glean from such documents information that might be persuasive.

Mr. Schechter concluded the 2018 Mosaic with a recommendation that we determine the human carrying capacity of our valley. He points out that we have already far exceeded a natural capacity by importing everything we use in daily life from food to electricity. If we lived like the original people here, we’d spend some time in the mountains when the hunting and gathering was best, and our numbers would be few.

While working for the U.S. Forest Service for decades I wrestled with the concept of carrying capacity when it came to human recreation use in backcountry and wilderness areas. The idea was too simple: the land’s capacity to handle us without damage depends on how we behave.

Up to an unknown tipping point, numbers weren’t the problem. The fact that the contents of our backpacks, like the goods we import for our homes, allowed large numbers of us to occupy wild country with ease was not part of the equation. We looked instead at resource conditions and how much change was considered acceptable. Sure, you can get 100 people camped around an alpine lake before someone is pushed into the water by crowding – is that the carrying capacity? Or are we trying to maintain some peace and quiet and not allow the entire lakeshore to be trampled?

The national forests where I worked in Greater Yellowstone—the Bridger-Teton and Custer-Gallatin— were far enough below any numbers-based carrying capacity that we could largely rely on asking people to practice no-trace camping. The number of rules were, and are, minimal—limits on party size, setbacks from water, and in a few cases a ban on campfires at high elevations where fuel is scarce.

We still get by with these rules, but that could soon change. In wildland areas near large cities, the only way to maintain some semblance of a backcountry experience and environment is to limit numbers.

I guess that number, depending on how the people are distributed, is the carrying capacity until we no longer mind jostling for a tent site and don’t care if the lake shore is a ring of bare, compacted ground.The same seems to go for our communities. We can and do pack more people in, but how much crowding and noise is too much? The main question to me is not whether we care, for it’s obvious that many of us do. But what can we do about it?

We have many publications and reports at our fingertips that offer good summaries of specific problems and steps needed to address them. And important steps are being taken to hang onto what is precious and irreplaceable in our environment. But not everyone has the same definition of precious. Property in Teton County is increasingly seen as an investment or a place to live in luxury. Voluntary low-impact lifestyles are few and the people who live them are seen as Luddites or cranks.

The Jackosn Hole Conservation Alliance’s State of Wildlifereport focuses on a few species that represent habitats of great concern: greater sage grouse for sagebrush/bunchgrass steppe, northern goshawk for the mature forests. How many people in the community have seen the grouse strutting or a goshawk maneuvering with lightning speed through dense branches? If they have no clue about these species and what they depend on, they are unlikely to care about them.

“In wildland areas near large cities, the only way to maintain some semblance of a backcountry experience and environment is to limit numbers. What percentage of the growing population of Jackson Hole knows that we have a designated wilderness in our back yard, or even what wilderness means, other than a place where ‘I can’t ride my bike?'”

What percentage of the growing population of Jackson Hole knows that we have a designated wilderness in our back yard, or even what wilderness means, other than a place where “I can’t ride my bike”?

Our county presses on, doing its best to balance the needs of wildlife with human growth. It has worked with the highway department to place safe wildlife crossings under some roads, and sponsors with non-profits a system of conservation easements that have resulted in the protection of close to 24,000 acres, many of which are adjacent or in proximity to the Snake River and its historic floodplain.

The Teton Conservation District has initiated a volunteer trout-friendly lawns program which helps landowners maintain their grounds without sending harmful runoff into streams.

And I must also mention the county’s land development regulations. We have specific standards for wildlife-friendly fencing and the maximum size of buildings allowed in the rural-zoned parts of the county. Or, we did.

During the most recent session of the Wyoming state legislature, representatives from distant counties decided to tell Teton County what it can’t require to protect its precious wildlife resource. This includes the above-mentioned direction on wildlife friendly fencing and retention of the rural character of areas zoned so through limits on structure size.

We deal with so many hurdles to finding the balance between growth and preservation it’s easy to become jaded and discouraged. You never know when progress will be thwarted through legislative meddling, the purchase of a large and habitat-rich property by an entity bent on altering it completely (and most often legally), or the overwhelming in-migration of more people who want to live in the region for the same reasons most of us live here already. Again, who can blame them? But how can we welcome more while preserving what most of us love?

Each of us has to answer in our own way. I try to do everything I can think of, making lifestyle choices and engaging with my elected officials. But I don’t want to lecture or tell anyone else what to do, which is why I feel I must end this essay with a question. One thing’s for sure, we’ll be challenged more as time passes, and I hope we are up to it.