On the third day of a six-day trip down the Yampa River, we started walking. A slurry of flash rainstorms had rattled our tents the night before and raised our hopes the river would rise. It didn’t. When our bottoms ground to a halt on the riverbed, we grudgingly rolled up our boats–inflatable one-person kayak-shaped pack rafts—shouldered our 60-pound backpacks and started lumbering down the naked channel. If we were going to reach the end of the river before our own food ran out, we had to keep moving.

“Walking has to be faster,” said my companion Len Necefer, a former professor of engineering at Northern Arizona University.

With only a few small dams and diversions, the 250-mile-long Yampa is one of just a few free-flowing rivers in the United States and the longest in Colorado. Beloved by rafters for its wild whitewater in spring, it’s a lifeline for ranchers and residents in northern Colorado. But it’s also the main tributary to the Green River and a major supplier to the Colorado River system, which supplies water to 40 million people and irrigates five and half million acres of farmland in seven states.

Aerial perspective of the oxbow maze of the Yampa as it winds through Dinosaur National Monument. In the center left sits a visible sandbar that typically creates an eddy habitat, called Mather’s Hole, where frogs are abundant and create croaking symphonies at night.

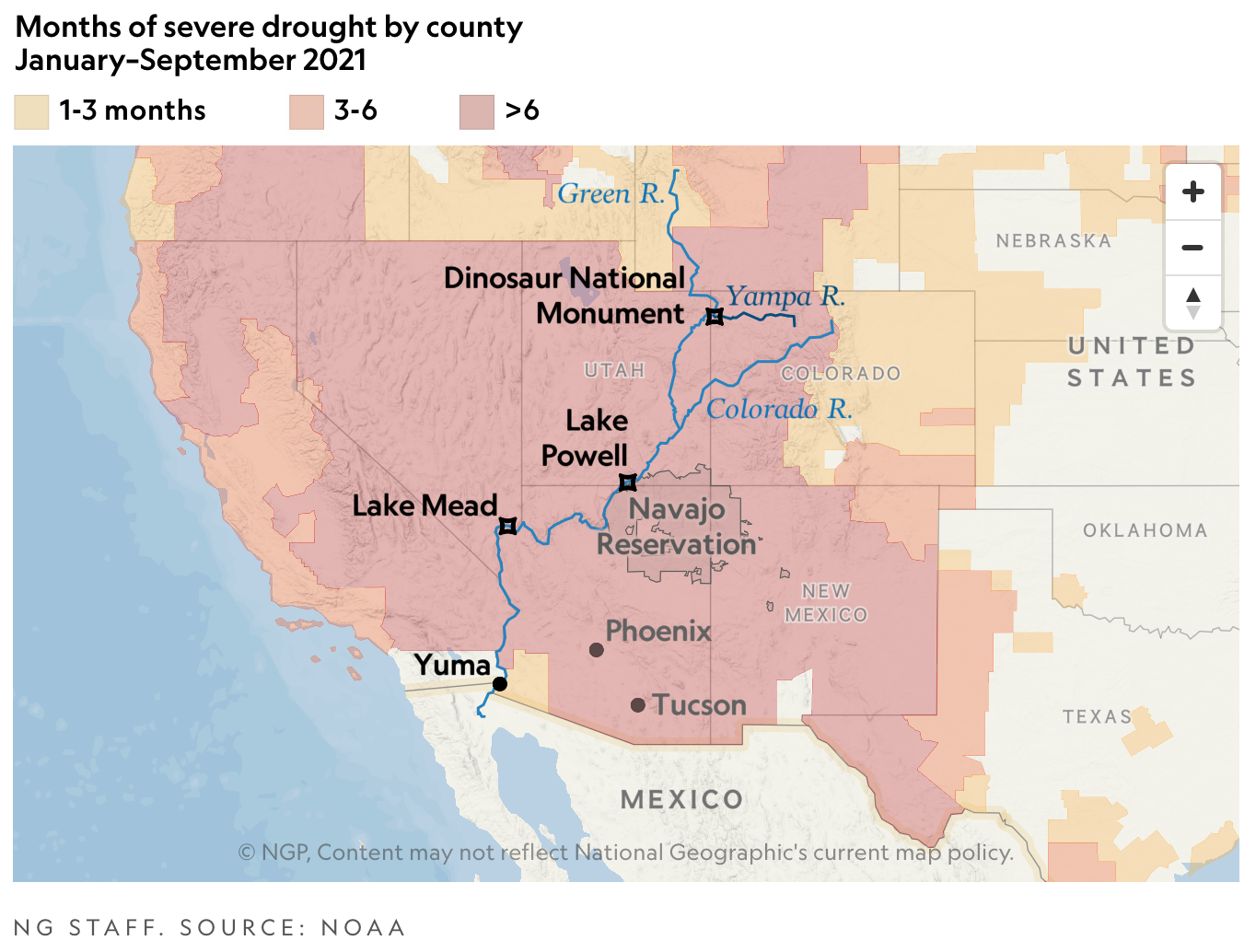

This year a record-smashing drought, the latest in a two-decade-long megadrought, has fallowed alfalfa fields in Colorado and left abandoned boat ramps and “bathtub rings” on reservoirs downstream. Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the U.S., fell to a record low, triggering the first mandatory water restrictions across Arizona and Nevada.

“This year is a millennial scale drought, as significant as any on a 1,000-year time scale, and the Yampa is a microcosm of the bigger picture,” Jack Schmidt, a watershed scientist at Utah State University who has researched the Yampa for 30 years, told me before we left. “The only difference is its wonderful naturalness. The Yampa is the most priceless river piece of the Colorado River system.”

Our goal was to travel the last 50 miles of the river through Dinosaur National Monument, to see how even a wild river inside a national park was struggling to stay wet. The trip would foreshadow what might be to come for many western rivers as the climate changes.

For weeks before we left, I monitored stream flow gauges, wondering if we might see the river dry up entirely. On August 18, the hydrological curve of the Yampa at Deer Lodge, where we planned to put in, plummeted to 45 cubic feet per second (cfs)–one of the lowest levels in recorded history. According to U.S. Geological Survey data, the average flow on that day over the last 36 years is 330 cfs. I warned Len to pack as lightly as possible and be prepared to walk.

On the morning of August 20, after Len sang a Navajo prayer and gave a small cornmeal offering for the river and our safe passage, we shoved off. That morning, the river gauge doubled to 70 cfs. Either some rain nearby was helping, or ranchers upstream had shut off irrigation ditches to cut hay. Or maybe someone was listening to Len’s prayer. Whatever its source, the surge added an inch of floatable depth to the ankle-deep ripples before us.

But just a quarter mile from our put in, the river channel braided, the water thinned, and our little rubber boats screeched to a stop for the first time in the sandy sediment.

“It has to get better downstream,” I said.

Necefer navigates a field of boat-popping boulders, carrying his heavily loaded pack raft, the gear packed inside the tubes. At higher water levels, this section creates splashy rapids.

Top: Necefer makes coffee at camp after patching his boat.

Bottom: Despite incredibly low water, Warm Springs rapid, notorious for flipping large rafts at high water, still throws enough punch at low water to flip a packraft.

Over a decade ago, I traveled the length of the Colorado, documenting its flow from the headwaters in the snowcapped peaks of the Rocky Mountains, where I grew up, to its parched terminus in Mexico. For six million years, the Colorado River flowed to the Gulf of California. But after Americans discovered that our engineering skills can bring the river to us, by means of reservoirs and aqueducts, we cut it off from its desert delta. The river stopped reaching the sea in the late 1990s.

I witnessed this firsthand, and I was alarmed to see the mighty, iconic river, the architect of the Grand Canyon, wither into a frothy brown puddle of plastic garbage and muck some 100 miles from the ocean.

To my amazement, few people knew. The untimely death of the river occurs in a region few visit, south of Yuma, Arizona. Upstream, fountains still flow, sprinklers spray, and the greening of the desert continues, all over the Southwest, as it has for decades.

But today, because of overallocation of the river, rising water demands, and a hotter and dryer climate, it’s as if that forgotten dry delta were spreading upstream, like a train wreck in slow motion. With diminishing reservoirs, the incredible shrinking Colorado River watershed looks terminally ill.

Len Necefer was raised in a small town on the Navajo Reservation in New Mexico, in a family of traditional healers, and he’s acutely aware of water scarcity in the West. Many on the reservation lack running water and depend on fickle wells—and many of those wells tap into aquifers connected to the greater Colorado River system.

After years spent studying water and energy, Len decided during the pandemic to focus on more hands-on experiences documenting the challenges of climate change. He left his job in academia to dedicate all his energies to Native Outdoors, a network of Native American athletes, activists, and filmmakers that he founded in 2017 to provide “a voice for the plants, animals, and land.”

“I can’t believe this is my drinking water in Tucson,” Len said under the sweep of starlight on our second night. After a pause, he added, “It is so sad to see it so low.”

Boaters wait years for permits to raft the Yampa at high water and often kiss Tiger Wall for good luck as they float past toward Warm Springs rapid just downstream. We hiked by the “tiger stripes” in ankle-deep shallows, and forgot to kiss the wall, and we flipped a raft downstream.

On the very first day we had repeatedly been forced to walk. For 12 miles we dragged, hiked, carried, splashed, scratched, scooched, whined, and rarely floated downstream.

After climbing in and out of our boats hundreds of times, Len looked at me and said, “I didn’t realize this was going to be a week-long Yampa cross-fit class. I’ve already done a million sit-ups.”

But the third day was the most dispiriting. By noon, after two miles of hiking the riverbanks, we quit and switched back to dragging our boats. Hiking was faster, but with our heavy loads it was too challenging to navigate thick brush and loose terrain filled with thickets of poison ivy. We re-inflated our crafts and tried to navigate the trickle of river percolating through mazes of boat-popping boulders. With normal flows, such rocky stretches would create fun, splashy rapids.

Sometime around late afternoon, Len punctured his boat on a rock just below the surface. Forced to call it a day, we camped on a sandbar and assessed our predicament.

“I am now a PhD in boat-popping too,” Len joked as he sat in the shade of a juniper tree, inspecting his battered vessel.

Despite our deflated morale, we had reached the meandering oxbows where the Yampa flattens and slows. Here it steps into cathedrals of deep time, running alongside 500-foot vertical walls that drop right to the riverbank.

Just a hundred yards from the shore, the land looked cooked. A bit downstream, I walked a dry river channel. Dead crawfish, already bleaching white, lay scattered near rocks and cracked silt beds. A haunted silence hung in the air. On past trips here, when the river was higher, I had marveled at the symphonies of frogs at night. During the day, the low rumble of the river and the buzz of bugs had been a constant presence.

Now the soundscape was empty.

Some wildlife appeared occasionally. A gang of male sheep stood and lay in the river near the shore, unfazed by our passing. A bald eagle soared high around the cliffs. Fresh mountain lion tracks shadowed the river, and a peregrine snatched a fish right in front of me at sunrise. But few fish rose to the surface, and the deer looked thin, their ribs visible. The drought quietly gnawed at everything.

STRESSED WILDLIFE

Left: Above, a sheep wades in the shallows. At bottom, moss dries inside a typically wet slot canyon behind “Cleopatra’s Throne” a prominent rock outcropping.Right: At top, habitat for this northern leopard frog is normally wet, but has been dried out. Below, dead crayfish bleach in a dry river channel.

The Little Snake and Yampa rivers meet upstream of Deer Lodge, where Yampa water levels are at some of the lowest ever.

In the 1950s, the Yampa made more noise than it does today—politically. Despite its wild remoteness, Dinosaur National Monument and the rivers that shaped it became the center of a national fight in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation proposed a dam just below the confluence of the Green and the Yampa to store the water of both rivers.

If completed, it would have flooded much of the Green and the lower Yampa we had traveled, including archaeological sites and pictographs attributed to the Fremont people who roamed the region 1,000 years ago. Conservationists opposed the project as an encroachment into the National Monument. After much national debate, the project was abandoned in 1955—in favor of Glen Canyon Dam, which formed Lake Powell, drowning less-protected lands downstream, on the main stem of the Colorado.

Today Lake Powell, America’s second largest reservoir, sits at its lowest level since construction of the dam. Water managers upstream are releasing water from smaller reservoirs, reducing their levels to all-time lows to help fill Powell. Many experts fear it could fall below the level required to turn the hydroelectric turbines and generate electricity for 5.8 million homes and businesses; in late September, after Len and I got back, the Bureau of Reclamation announced a one-in-three chance of that happening in 2023.

On the Yampa, Len and I had more immediate concerns—for starters, would his raft hold air? Thankfully, Len’s boat doctoring worked. The oxbows snaked west, creating a few pools just deep enough to paddle. Every few hundred yards, we met gravel ledges and dragged our boats down the trickle that slowly sustained the next pool. We moved roughly two miles an hour.

The next day, surprisingly, the Yampa nearly vanished, most likely into a thirsty water table below. Damp sandbars filled most of the channel now. For hours, we inched forward, often on foot. Around one bend we marveled at “Tiger Wall,” a 200-plus-foot-tall sandstone cliff with black stripes of desert varnish created by moisture in a wetter era.

Boaters who wait years for permits to raft the Yampa at high water often kiss this adored wall for good luck as they float past. We hiked by the tiger stripes in ankle-deep shallows.

Moonrise over the final pools of the Yampa before it meets the Green. Thanks to Colorado’s endangered fish program, which releases flows from a reservoir for the river to sustain native species like the humpback and bonytail chubs, the pike minnow, and the razorback sucker, this final stretch had some water when other Colorado rivers had run dry

On the last morning, Len and I drifted the last two miles in our boats, brushing the river bottom only once. We relished the lazy moments. At the confluence with the Green River, we saw its comparatively powerful current of 1,800 cfs, swollen by cold water released from the Flaming Gorge Dam, racing downstream to keep Lake Powell from shrinking further.

Back home, I spoke to some of the angels that help keep the Yampa itself flowing. Jojo La, an endangered species specialist with the Colorado Department of Natural Resources (DNR), provides the last line of defense for the river’s four endangered fish. When the gauges plummet toward zero, the DNR releases pulses of Colorado-owned water from Elk Head Reservoir. The day before our trip, it turned out, La’s team had conducted a controlled release intended to keep the river alive with a targeted flow near 100 cfs. Without it, we would have most likely been forced to walk the entire trip.

During another severe drought in 2018, the endangered fish program started coordinating with other water users, from power plants to ranchers.

“Every water sector is pitted against the other,” said La, who grew up on the banks of the Yampa. “But now we have no choice but to work together. We have had to get really creative.” He hopes the Yampa can be a model of collaboration for others, because the “same story is happening in their river basin too.”

Mickey O’Hara, program director with the Colorado Water Trust, a group that uses legal tools to keep water in rivers, said collaboration saved the Yampa this year. “2021 was bad, but it could have been a lot worse,” he said. “Unlike other rivers, the Yampa didn’t run dry.” There will more years like this one, he predicted.

As Len loaded up his van to head home, I asked him what he thought of his first pack raft trip.

He smiled and said, “I have a lot of work to do. I need to inform people back home of the status of their drinking water and where it comes from.”