Recent grazing decisions continue to risk Southwest Colorado’s bighorns.

On a recent October morning, a single-engine plane dipped and jerked in a turbulent wind. A small group of conservationists and policy advisors, accompanied by my photographer and me, had all packed into a tiny EcoFlight to fly over a terraced expanse of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. Our pilot took a sharp turn east. The plane rumbled; our shoulders bumped and our cellphones shook as we took blurry photos of snow-capped mountains. We were at the apex of our route, a 126-mile loop over San Juan, Ouray and Hinsdale counties. Directly below us was Hensen Creek, a place that Terry Meyers, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Society, called “ground zero” for bighorn-domestic sheep conflicts in southwestern Colorado. He put it bluntly: “We’re looking down on a ticking time bomb for a mass die-off of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep.”

From the air the landscape is pristine, foreboding, disquieting. The peaks of Handies and Redcloud, two 14ers, loomed just below eye-level as we flew past. But the fight on the ground, a long-protracted battle between the wool industry, sheep grazing and bighorn sheep advocates, is anything but quiet. For years, Meyers and other bighorn advocates, including groups like Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and Great Old Broads for Wilderness, have fought Colorado land-management agencies over decisions to allow domestic sheep to range on bighorn habitat. The risk of a mass bighorn die-off, they say, is too high.

Scientists have long warned that domestic sheep — which carry a bacteria known as Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, or M. ovi — pose a deadly threat to their wild counterparts. The bacteria passes from domestic carriers to wild sheep and often causes pneumonia and death. Most domestic sheep carry M. ovi without getting sick, but bighorn sheep are highly susceptible to it, a finding affirmed years ago by scientists and acknowledged by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. If a bighorn sheep contracts M. ovi and brings the pneumonia back to its home range, the infection can spread to entire herds and lead to sweeping deaths. Yet decades of controversial decisions of federal and state agencies have enabled ranchers to continue leasing allotments as summer range for their stock, including high-risk pastures like Hensen Creek, where bighorn and domestic sheep have been known to mix.

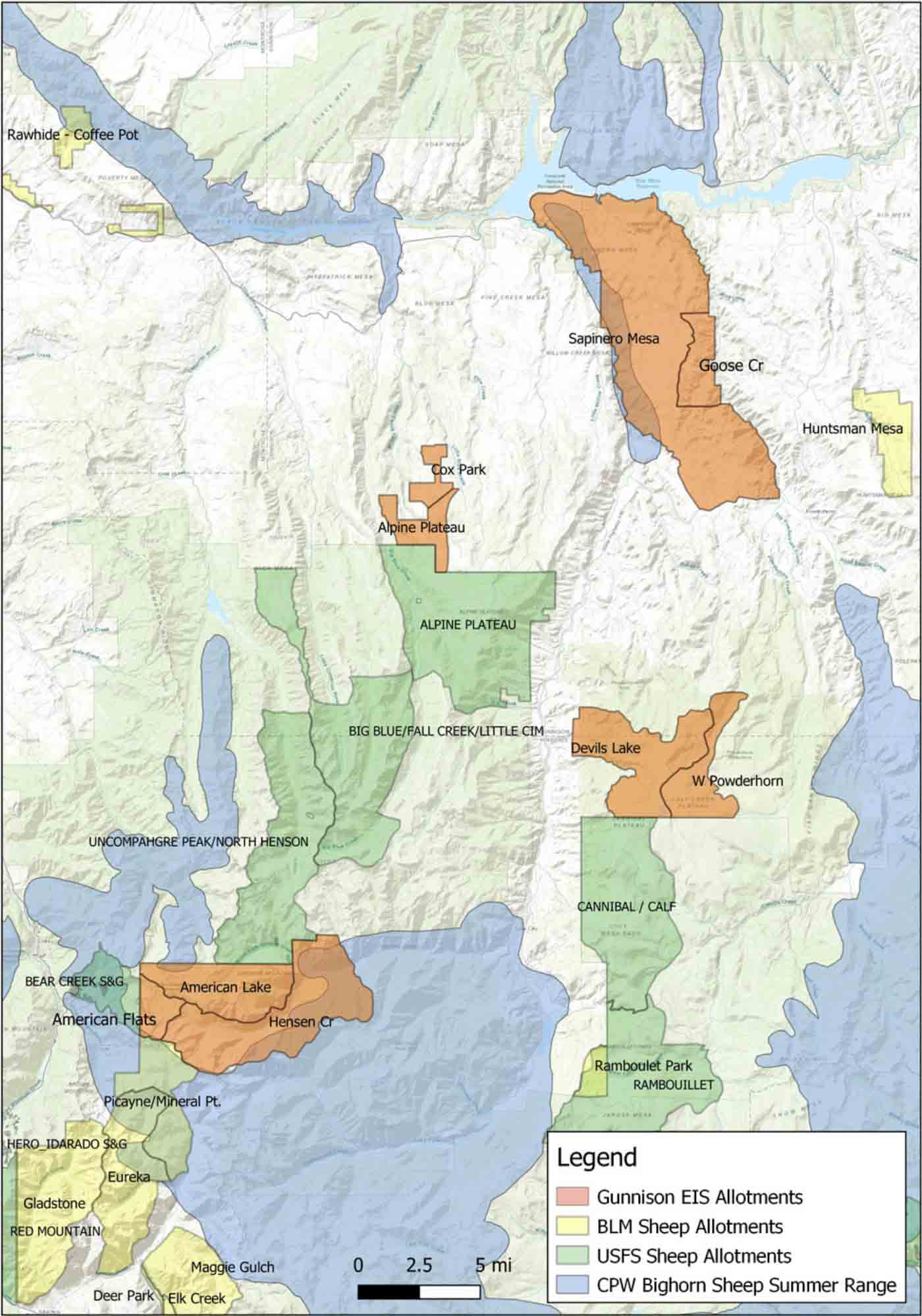

In late August, the Bureau of Land Management’s Gunnison Field Office, which administers grazing permits near Hensen Creek, announced its decision to continue to allow sheep grazing in the area. The allotments overlap with the range of one of southwest Colorado’s “Tier 1” Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep herds, a Colorado Parks and Wildlife designation that means the herd is endemic to the state and of conservation management priority.

The BLM’s decision covers nine domestic sheep-grazing allotments across the Gunnison Basin and the surrounding counties, Hinsdale and Ouray — more than 65,000 acres all told. The agency maintains that there is sufficient separation between the species both with regard to distance and timing. “Forays, for the most part, happen during the fall when we are not grazing domestic sheep,” said BLM wildlife biologist Kathy Brodhead. “But those bighorns are not tied to that boundary in any way.”

Bighorn sheep of both sexes foray, or travel significant distances outside of their home range, according to the Forest Service’s “risk of contact” model, which provides the best available science for maintaining adequate separation between domestic sheep and bighorn herds. These journeys occur at any time of the year, though rams increase their foraying behavior during breeding season.

But the BLM’s decision does not account for forays by bighorn sheep outside of the rut. And such forays have been documented. “Bighorn sheep will go just about anywhere that they want to,” said Eric Edgar, a volunteer observer for the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Society. Edgar has observed bighorn sheep and domestic sheep in proximity to one another. “Last year, I saw them in the same drainage — the Bear Creek drainage,” Edgar said. “There were two herds of domestics, and on the opposite side of the drainage was a group of bighorn lambs and ewes. They were inside of a mile away from the domestics.” A few years ago, one ram traveled for more than 60 miles across the rugged San Juan Mountains, through areas that Colorado Parks and Wildlife does not consider bighorn habitat. (The journey was covered by High Country News in 2018.) “There’s a bighorn population that’s on a grazing allotment that is not being accounted for in this decision,” Meyers said. “How can they make an argument that there’s no overlap there?”

“Bighorn sheep will go just about anywhere that they want to.”

“Risk represented by domestic sheep going into areas directly overlapping summer home ranges is of concern,” Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials wrote in response to the Gunnison decision. “But the greater difficulty in managing risk is with bighorns foraying out of summer ranges.”

Domestic sheep don’t always stay within the allotments’ invisible boundaries, which often lack fencing or topographical boundaries, such as rivers, canyons or cliffs. One permit holder, in a San Juan Landscape Rangeland Environmental Analysis by the BLM, told Colorado wildlife managers that he could not guarantee that his domestic sheep would stay within the grazing boundaries. “If authorized, this would place domestic sheep within a quarter-mile of an active bighorn sheep summer range area,” Meyers wrote in a letter to the BLM during its protest period.

High Country News phoned Bonnie Brown, executive director and spokeswoman of the Colorado Wool Growing Association, for comment, but did not receive a response before press time. In the past, Brown and other wool industry advocates have lauded decisions to maintain access to high-country domestic sheep pastures and promised to uphold their end of the bargain. “We want to cooperate,” Brown told me in 2018. “We want to minimize contact. Neither the Forest Service or BLM has mandated for zero risk, but we certainly agree to minimize risk and take appropriate steps.”

“If authorized, this would place domestic sheep within a quarter-mile of an active bighorn sheep summer range area.”

The BLM’s decision “does nothing to address this potential for co-mingling,” wrote Dan Parkinson, the Southwest director for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, in a recent letter disputing the decision. “As a result of direct overlap or very close proximity of areas used by bighorns and domestic sheep in the project area, interactions between the species are to be expected.”

In an August 2019 comment letter to the BLM Gunnison Field Office, part of the environmental analysis, Colorado Parks and Wildlife wrote that it had documented 25 stray domestic sheep occurrences, 34 bighorn forays, and seven co-mingling events between bighorn sheep and domestic sheep within the analysis area.”

The BLM’s decision has already gone through a 15-day protest period. Now, the agency must evaluate the comments and respond — a process that sometimes takes months or languishes for years — before a final decision is announced.

Meyers sat shotgun on the flight during the warm October morning. Like all of us, he wore seafoam-green headphones and spoke into a small microphone that broadcast into the other headsets worn by passengers inside the tiny cabin. His voice had the crackly cadence of a walkie-talkie. He called the decision “an embarrassment to that BLM office.”

“Based on the comments that CPW have provided on this analysis and the issues they have identified — which the BLM is largely ignoring — is an embarrassment,” Meyers told me later. “For the professional biologists in that office who may understand this issue but are unable to make a different decision, well, this is my opinion: As a biologist, I would be embarrassed to work for that agency.”

Paige Blankenbuehler is an associate editor for High Country News. She oversees coverage of the Southwest, Great Basin and the Borderlands from her home in Durango, Colorado. We welcome reader letters. Email her at paigeb@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.