THE HISTORY: In the 1980s, a site on the edge of Canyonlands National Park was a main candidate to become the nation’s nuclear waste dump.

THE REPEAT: Over the last few years, Energy Fuels has been reprocessing nuclear waste from around the world at its White Mesa Mill on the edge of Bears Ears National Monument, making it a de facto nuclear waste dump.

THE CONTEXT: For four decades, America’s nuclear waste was stored and disposed of haphazardly and dangerously. In 1982, Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, requiring the Department of Energy to come up with a national repository for spent reactor fuel and other waste. The long list of possible sites, released shortly thereafter, included Yucca Mountain in Nevada, the Hanford Site in Washington, a couple of sites in Texas, and the Paradox Basin in southeastern Utah.

The Paradox possibilities included the uranium mining hub of Lisbon Valley, Elk Ridge—the home of Bears Ears, the Salt Valley north of Moab, and a place called Gibson Dome near the junction of Lavender and Davis Canyons. Of these, only Gibson Dome made the short list, and an effort to establish America’s nuclear waste dump on Canyonlands’ doorstep commenced.

Many Utahns, having lived through decades of nuclear fallout from upwind weapons testing and suffering from illness due to the uranium mining and milling that had occurred in their backyards, were appalled. The commissioners of San Juan County, especially a former uranium miner named Cal Black—sometimes called the Original Sagebrush Rebel—were delighted.

The construction of the facility would employ over 1,000 people, and the operation nearly as many. Black believed that with a national waste dump in place for spent reactor fuel, the nuclear power industry—and therefore San Juan County’s uranium mining industry—would be revived. In an open letter published in the San Juan Record in March 1982, the San Juan County commissioners wrote: “We support such a facility and are opposed to Canyonlands National Park or archaeological sites in the area used to preclude the repository.” Black then went on to tell a Salt Lake Tribune reporter that tourists would enjoy visiting a nuclear waste dump, just as they reveled in seeing the gargantuan Bingham Canyon open-pit copper mine and visiting the Mormon Temple in heavily polluted Salt Lake City: “If pollution hurt tourism, then Temple Square in the heart of the state’s worst pollution, and Kennecott, one of the worst blights on the environment, wouldn’t be the state’s number one and number two tourist attractions.”

Even with that kind of marketing, Black wasn’t able to enlist much support from outside the county. Former uranium boomtown Moab had by then grasped on to the tourism and recreation economy, motorized and unmotorized alike, and many of its citizens were not too psyched about having a nuke dump on their doorstep and waste-laden trucks or trains rolling through the center of town. It wasn’t just about the radioactivity, either: the facility likely would require its own coal-fired power plant, a rail line from Moab, and would use as much as 1.5 million gallons of water per day.

The Sierra Club, Earth First!, no-nuke activists, and national park advocates launched a campaign, Don’t Waste Utah, to rally the public to oppose the plan. Utah governor Scott Matheson, a Democrat, went from being skeptical to outright opposed; his Republican successor ended up in opposition, as well. Black and his colleagues were enraged, and the county staked 2,000 mining claims in the repository study area out of spite. It didn’t work. Opposition to the dump continued to grow, and in 1986 the final environmental assessment was released, relegating the Canyonlands site low down on the list of possibilities, with Yucca Mountain in Nevada rising to the top. The Chernobyl disaster and then the end of the Cold War further diminished Utah’s uranium mining industry. Cal Black, known for wearing a uranium-clasped bolo tie, died of lung cancer in 1990.

Now, Black is finally getting his wish for a nuclear waste dump in his home county, though it’s not quite as grand as what he had envisioned.

The White Mesa Mill, located between the Ute Mountain Ute community of White Mesa and Blanding, was constructed in the 1970s, when uranium mining still was going gangbusters in southeastern Utah. Then the Cold War ended, meaning less uranium was needed for bombs, the nation stopped building nuclear power plants, and globalization opened channels to cheaper uranium from overseas. Slowly, the domestic uranium mining industry withered, virtually going dormant in the last few years. The White Mesa Mill, however, has hung on—barely, and is now the nation’s only remaining active uranium mill.

Thing is, they aren’t processing uranium, at least in the conventional sense. They are processing “alternate feed materials,” which is to say, they are taking uranium-bearing waste from other facilities, running it through the mill, and then dumping the stuff in their on-site disposal piles and ponds. While the process can recover minute quantities of uranium, the real money comes from providing a disposal site or, as Energy Fuels puts it:

“… the generators of the Alternate Feed Materials are willing to pay a recycling fee to the Company to process these materials to recover uranium and then dispose of the remaining by-product in the Mill’s licensed tailings cells, rather than directly disposing of the materials at a disposal site.”

In fact, these recycling fees—i.e. waste disposal fees—made up the bulk of Energy Fuels’ revenue over the past few years, according to SEC filings, totaling $6.7 million, compared to just $66,000 from uranium sales and $3.7 million from vanadium and rare earth sales, combined. That makes it, according to a recent report from the Grand Canyon Trust, “America’s cheapest radioactive waste dump.”

Evidence indicates it’s not the safest dump, either. The disposal ponds have leaked and contaminants detected in shallow groundwater beneath the mill. More recently, aerial photos have shown that some of the waste remains uncovered by water. This same negligence led the EPA to prohibit the mill from processing material originating from Superfund sites.

For more details and history, read the Grand Canyon Trust report (with excellent graphics) and Jessica Douglas’s feature story from last year for High Country News.

THE HISTORY: In 1971, Peterson Zah, who would go on to become Navajo Nation President, said: “The formula is very simple and politically sound. Indian land, Indian coal, and Indian water will generate Indian power. The power will be shipped across Indian lands to Albuquerque, Phoenix, and Los Angeles. The cities will get more and more power at no cost to their environment. The result will be Indian pollution.” Zah was referring to the raft of coal power plants being built on or near the Navajo Nation at the time. The power bypassed the communities nearest the plants, while those same communities shouldered nearly all of the burden of the pollution. Peter Montague, a prominent environmental advocate, called the then-new Four Corners Power Plant on the Navajo Nation, “the greatest single public health hazard in the Southwest and perhaps in the Nation—possibly even in the world.”

THE REPEAT: A new study in the American Journal of Public Health found that air pollution may be decreasing nationwide, but it is not doing the same in predominantly Indigenous communities. As a result, Indigenous communities are bearing a disproportionately high share of the pollution burden. In the researchers’ words:

Our findings suggest that socioeconomically disadvantaged communities experience disproportionate burdens of environmental hazards, such as ambient air pollution, contributing to adverse downstream health effects. The substantially larger decrease in PM2.5 concentrations in non–{Indigenous} versus {Indigenous}-populated counties highlights a need to enhance enforcement of air quality regulations and restrictions to PM2.5 emissions on tribal territories, surrounding regions, and other areas with large populations of {Indigenous} people.

In other words, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Back in 1971—the occasion was a Senate hearing to discuss “Problems of Electrical Power Production in the Southwest—Zah had quite a bit to say, most of it still relevant today, we include some of his words:

The truth is that the ever-increasing use and demand for power is a sickness. Something has gone wrong somewhere with the American public’s value. This destructive, even suicidal, trend must be reversed at once for the sake of everyone, white men and Indians alike. But if the trend is not to be reversed, it should be the users of the power that suffers the consequences. The users should produce their own power in their own backyard and live with the resulting ruination of their own environment. Let the Indians alone. If the environmental destruction of parts of America is all but irreversible, as some scientists maintain, at least the Indians of the American Southwest may escape this fate and be able to survive an ecological disaster which was not their doing. …

And then, this zinger(!):

In essence, then, the relationship between the southwestern power complex and the water rights of the Navajo tribe is this: Navajo coal mined from Black Mesa will be burned at the Navajo Generating Station on the Navajo Reservation in order to pump Navajo water from the Colorado River to the central Arizona project.

The Four Corners Power Plant continues to operate. The nearby San Juan Generating Station is slated for retirement later this year—though that could change if Enchant Energy takes over and continues running it for years without carbon capture. The Navajo Generating Station and the associated Kayenta Mine on Black Mesa shut down in 2019. But even still, the problems persist

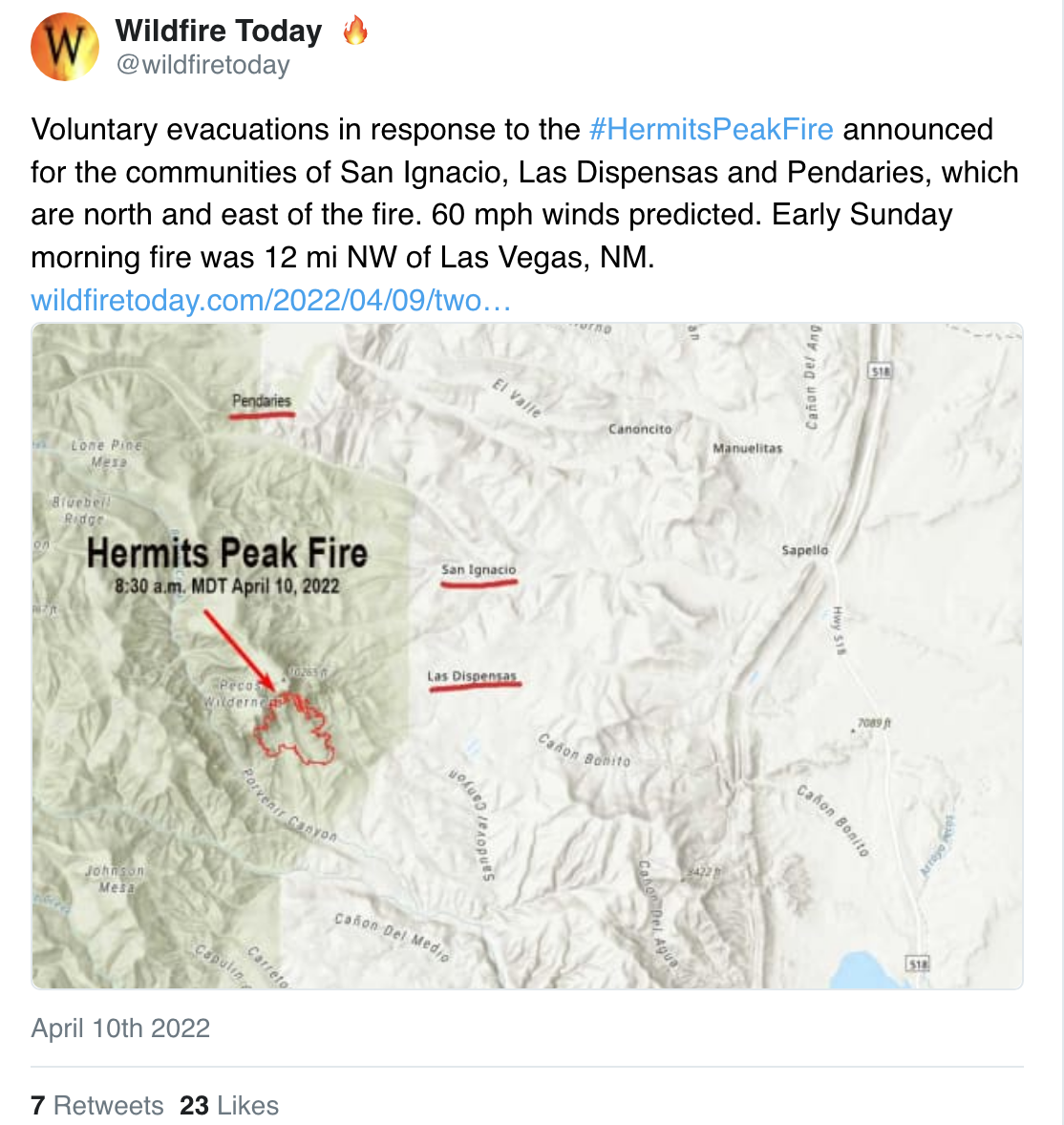

Fire season is here already, or perhaps it just never left. The latest blaze began as a prescribed burn near Hermits Peak in New Mexico that was whipped out of control on a hot, windy April day. It had grown to about 700 acres over the weekend, triggered voluntary evacuations, and brought up memories of the devastating Cerro Grande Fire of 2000, another prescribed burn gone bad.

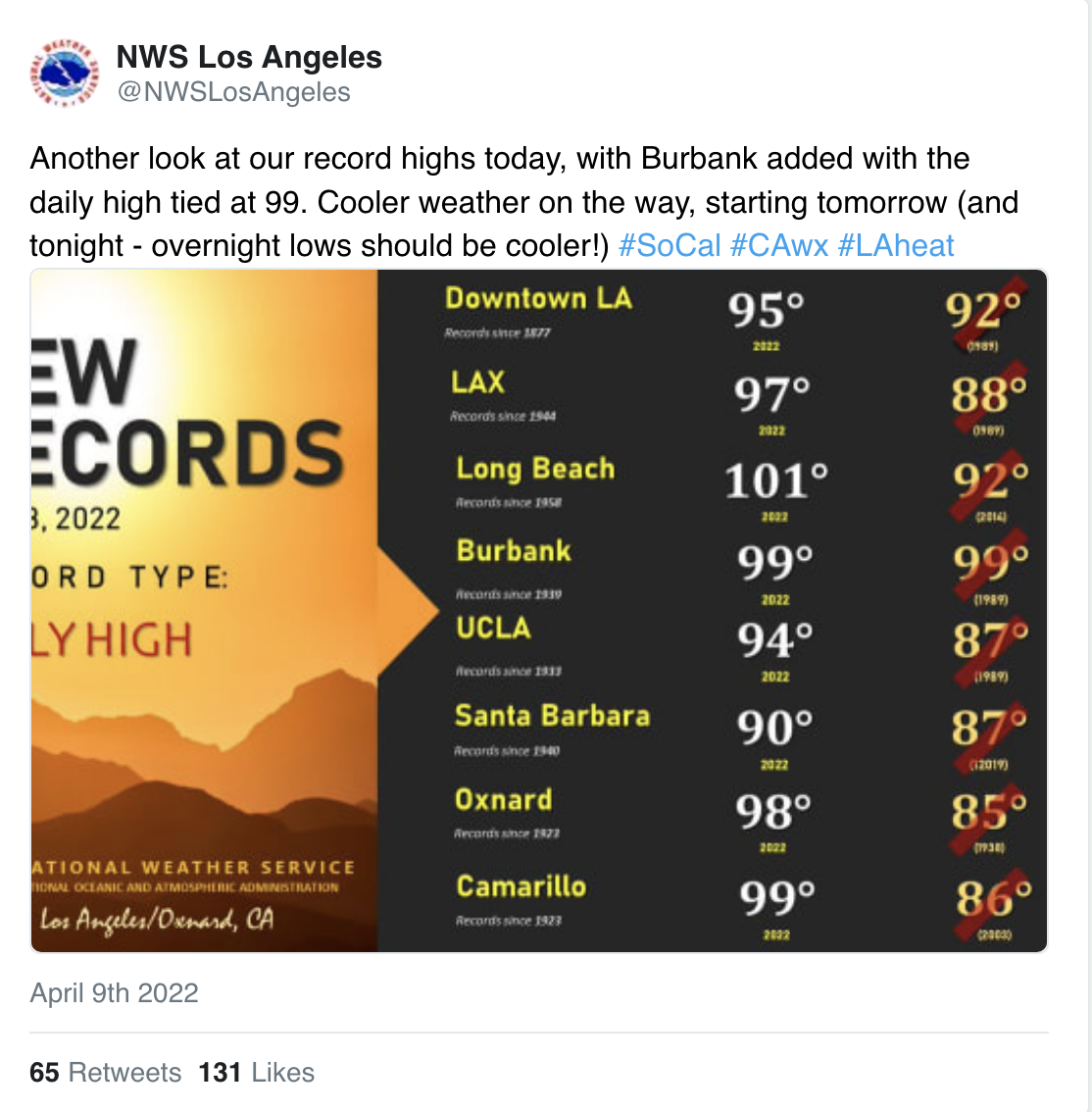

While many areas got near-average snowfall over the winter, the white stuff’s melting quickly and vegetation drying out due to a bit of a heat wave that brought temps like this to the L.A. area

Meanwhile, even as the National Weather Service warns of a coming winter storm for the mountains, it’s also got a critical fire weather alert in place for much of the Southwest.

If you’re interested in wildfire, and you really should be, given how big of a part of life it is in the Western U.S., you must subscribe to Jan Selby’s newsletter, Fires. Selby is a former hotshot and has great insights into the fire industrial complex and topics like the “fight for burning rights” covered in their latest missive. Check it out.

I’ve had a few readers bemoan the fact that the Land Desk is full of depressing news. And they’re right. So, from here on out, I vow to always add at least one uplifting—or at least not super-saddening—nugget from the West.

Today’s not-so-dismal news comes from Montana, where newly legal recreational marijuana sales have generated nearly $10 million in taxes in just three months, which means more cashola for public services. But here’s the really good part: Pot tax revenues are on pace to exceed those from severance taxes on coal.

It just goes to show that the extractive industries’ “golden geese” can be replaced by much cleaner endeavors. New Mexico also just began legal recreational marijuana sales, including in Farmington, where an energy/economic transition is underway, if a bit haltingly.