This blog is co-written by Troy Honahnie, Jr., Hopi consultant, and Rachel Ellis, American Rivers

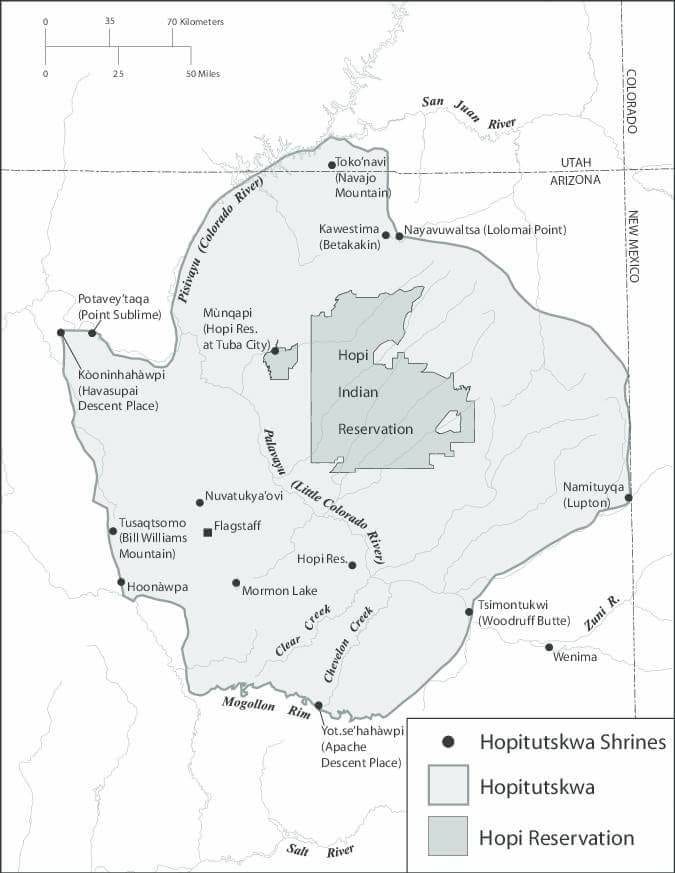

For two early mornings in Spring, Hopi leaders, elders, and advocates joined with EcoFlight, American Rivers, and the Grand Canyon Trust to fly over Palavayu, or the Little Colorado River. This is no small feat for a 340-mile-long river. The primary purpose of the flights was to offer Hopi elders and cultural leaders—the people who’ve mostly experienced Palavayu through song, culture, and religion—an opportunity to behold the river and Hopitutskwa, the Hopi ancestral lands, in their entirety and to engage in conversations about their protection.

Viewed from the air, an impressive landscape unfolds in which Palavayu (“red river”) flows through the center of Hopitutskwa. Nuva’tukya’ovi, the peaks near Flagstaff, rise to the West, still capped in snow in mid-April.

Hopitutskwa occupies much of the 17.3-million-acre Little Colorado River watershed. Flying towards the headwaters from Winslow, Homol’ovi—an ancestral Hopi settlement along the river—and Tsimontukwi, or Woodruff Butte, come into view. We observe the massive scale and impact of the three coal-fired power plants that operate exclusively on the groundwater below Palavayu. Notably, these stations withdrew a combined average of 36,100 acre-feet of groundwater per year between 2001-2005 and continue significant withdrawal to this day, directly impacting the river’s baseflow and communities downstream who rely on both the river and the Coconino aquifer.

When we turn and fly northwest towards the confluence with Pisisvayu, or the Colorado River, the layers and shadowed canyon of Öngtupqa—Grand Canyon—clarify in the early morning light. Soon we’re over Sakwavayu—Blue Springs—and then the site of the proposed Big Canyon Dam, a place which is as undeniably beautiful as it is undeniably inappropriate for a project that would pump billions of gallons of ancient groundwater to fill four reservoirs for the sheer speculation around cheap hydropower.

But, the flights facilitated much more than the viewing of the landscape. The experience generated conversation about how to advocate for the river and how to include elders in the process. It helped Hopi community members feel respected and included in the work to protect the river and provided an opportunity for them to share their expertise on the issues that are important to them. It supported younger generations of Hopi advocates in demonstrating good intentions and provided an opportunity to learn proper Hopi place names. It also helped to build trust between Hopi and non-Hopi partners.

“Lack of access to information—this is what is driving people’s concerns. No one has been communicating with us at Hopi or explaining what’s happening.”

Increasing access to information about threatened places, including creating opportunities to witness these places firsthand, is a critical part of conservation advocacy. Many of the participants in the flights were unaware of the Big Canyon Dam proposal and many more yet in communities along the Little Colorado River don’t have access to this information or what can be done. We’re working on multiple fronts to change that. One critical next step is that Hopi filmmaker, Victor Masayesva Jr., will be using footage gathered during the overflights in a forthcoming Hopi-language film titled “Sípapuni” about Palavayu and its attendant cultural landscape. The film will be shown in upcoming outreach events throughout Hopi villages and communities, encouraging all Hopi to engage in the effort to safeguard this incredibly important river.

We’re grateful to the Hopi Cultural Resources Advisory Task Team, Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, and Hopi Tribal Council for participating and to our partners at EcoFlight.