(Ecoflight) An aerial view of the Glen Canyon Dam at Lake Powell, Thursday, April 14, 2022.By Zak Podmore | Aug. 3, 2022, 11:21 a.m.| Updated: 2:08 p.m.

After a modest rise in June, the water level in Lake Powell is on its way back down.

The Bureau of Reclamation forecasts indicate it’s possible that Lake Powell could drop 37 feet by April to under 3,500 feet in elevation, a level where the Glen Canyon Dam would be dangerously close to losing its ability to generate hydropower.

The federal agency has announced a series of extraordinary actions and water cuts over the last several months to slow Lake Powell’s decline, and protecting electricity production at the dam is often cited as a primary concern.

But another issue looms in the background that has received far less attention, even though it could have much farther reaching — and potentially devastating — consequences for residents of the Southwest than the loss of hydropower.

According to a report released Wednesday by three environmental groups based in Utah and Nevada, the Glen Canyon Dam’s design could contribute to significant water shortages for the more than 30 million people who rely on Colorado River water downstream of Lake Powell in California, Arizona, Nevada and northwest Mexico with ramifications in Utah and beyond.

“The primary focus of this report is the antique plumbing inside Glen Canyon Dam,” said Zach Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council, which prepared the report with the Glen Canyon Institute and the Great Basin Water Network. “We wanted to put this synthesis together because we feel like the Bureau of Reclamation has not been forthright about why there is so much urgency around cutting this water.”

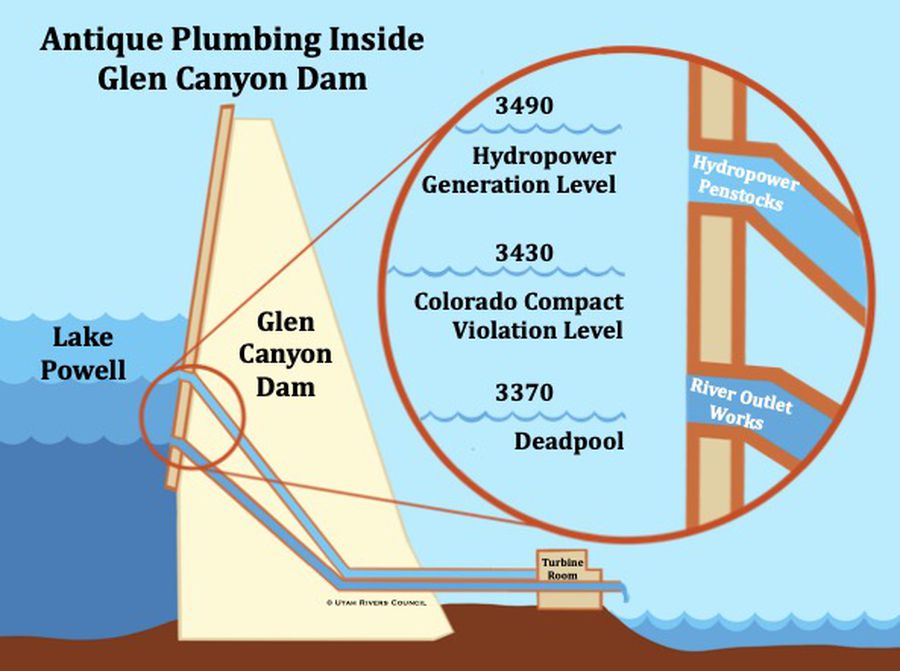

To explain the issue, the report gives a lesson in engineering. The 710-foot tall dam, which was completed in the 1960s, was not designed to operate for long periods when Lake Powell is filled to less than a quarter of its capacity, as it is now.

During normal operations, water is released through a set of eight hydropower penstocks that offer dam operators a wide range of flexibility in the amount of water that can be sent downstream. But Reclamation officials have indicated that the penstocks cannot be used if Lake Powell drops to 3,490 feet in elevation, 46 feet below the reservoir’s current level.

There is only one other set of outlets in the dam below the penstocks: four tubes known as the river outlet works that are located at an elevation of 3,370 feet, a full 200 feet above the Colorado River below the dam.

(Utah Rivers Council) A cross section of the Glen Canyon Dam with critical elevations marked.

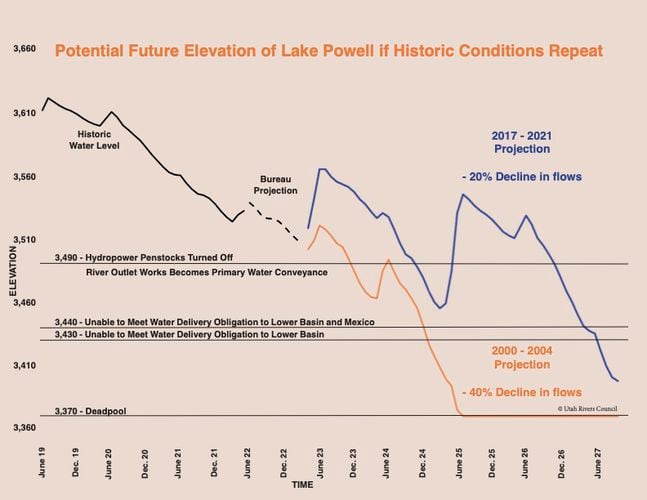

Drawing on engineering studies completed by the Bureau of Reclamation and a series of white papers published by Utah State University’s Center for Colorado River Studies, the report explains that the outlet works can release a maximum of 15,000 cubic feet per second, but that number begins to decrease as the reservoir drops below the penstocks.

If Lake Powell reaches 3,430 feet, dam operators wouldn’t be able to release enough water to meet minimum delivery requirements mandated under the Colorado River Compact of 1922 and subsequent agreements between water users in the basin.

At 3,400 feet, the maximum discharge through the dam would fall to 4,800 cubic feet per second due to a loss of pressure, or hydraulic head. Extended over a year, total releases would amount to 3.5 million acre-feet of water, less than half of the current annual water use downstream.

“Lake Powell is quickly approaching the point at which it may soon become physically impossible to pass enough water through the dam to meet the Upper Basin’s water delivery obligations,” the report states. “Such an event would likely be the most calamitous in the Colorado River System’s history, causing legal complications, economic harm, and a water supply crisis across the seven states and Mexico.”

Just how soon Lake Powell could reach elevations where this would become an issue is difficult to predict.

For decades, climate scientists have published studies indicating that climate change will likely result in decreased runoff in the Colorado River basin. Since the year 2000, flows in the river have been around 20% less than the last century’s average, which is a major factor contributing to Lake Powell’s decline.

In a peer-reviewed paper published in the journal Science last month, a team of researchers concluded that Lake Powell and Lake Mead could likely be stabilized near their current levels if water users agree to substantial, ongoing cuts.

The Bureau of Reclamation has given the seven Colorado River basin states until Aug. 15 to come up with a plan to reduce water use by between 2 and 4 million acre-feet next year. (By comparison, California, the basin’s biggest user, is currently entitled to 4.4 million acre-feet of water.)

But whether the plan will be enough to reverse the overall downward trend in reservoir storage depends on the size and duration of the cuts as well as water runoff.

Using a simple model based on past water conditions in the Colorado River, the environmental groups found that water shortages could occur below Lake Powell as soon as 2025 if conditions from the extremely dry five-year period from 2000 to 2004 were repeated. If future conditions are similar to the 21st-century average, Lake Powell may not fall below 3,440 feet before 2027.

The model is “not meant to be a prediction,” said Eric Balken, executive director of the Glen Canyon Institute. “It’s just to highlight the possibility of this happening…This system is in decline and [delivery shortages] are very much within the realm of reality.”

In an April letter to water managers, Tanya Trujillo, the Department of Interior’s assistant secretary for water and science, acknowledged that delivery shortages could soon become an issue below Lake Powell.

Below 3,490 feet in elevation, she wrote, “Glen Canyon Dam facilities face unprecedented operational reliability challenges, water users in the Basin face increased uncertainty, [and] downstream resources could be impacted.”

The environmental groups are calling upon Congress “to fund an emergency study by the Bureau of Reclamation to assess and address the engineering shortcomings of Glen Canyon Dam.”

They propose two potential solutions for further study: expanding the river outlet works to allow them to release more water at low reservoir levels and constructing new tunnels near the base of the dam to allow the reservoir to be drained completely should that be necessary.

The benefits, costs and feasibility of both options are complex and need to further review, the report stated.

Earlier this year, the Bureau of Reclamation said it would spend $2 million to study potential modifications to the Glen Canyon Dam, including retrofitting the river outlet works with turbines so that power could be produced at lower reservoir levels.

In response to questions from The Salt Lake Tribune, a spokesperson said Tuesday that the study is not expected to be completed until 2024.

The federal agency added that it was too soon to comment on whether the study would explore the feasibility and cost of expanding the river outlet works or constructing new bypass tunnels.

Balken stressed the urgency of the situation and the need for swift action, but he emphasized that the report was not meant to downplay the challenges water managers face at the Bureau of Reclamation.

“Their job is incredibly hard,” he said. “They’re faced with this really pressing situation. But every stakeholder in the basin agrees that the system needs to change… We’re asking for a study to make Glen Canyon Dam more adaptable and more flexible.”