For decades, the U.S. government has failed to test for chemicals and metals in fish. So, we did. What we found was alarming for tribes.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Salmon heads, fins and tails filled baking trays in the kitchen where Lottie Sam prepped for her tribe’s spring feast.

The sacred ceremony, held each year on the Yakama reservation in south-central Washington, honors the first returning salmon and the first gathered roots and berries of the new year.

“The only thing we don’t eat is the bones and the teeth, but everything else is sucked clean,” Sam said, laughing.

Her mother and grandmother taught her that salmon is a gift from the creator, a source of strength and medicine that is first among all foods on the table. They don’t waste it.

“The skin, the brain, the head, the jaw, everything of the salmon,” she said. “Everybody’s gonna have the opportunity to consume that, even if it’s the eyeball.”

Sam is a member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. They are among several tribes with a deep connection to salmon in the Columbia River Basin, a region that drains parts of the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, southward through seven U.S. states into the West’s largest river.

It’s also a region contaminated by more than a century of industrial and agricultural pollution, leaving Sam and others to weigh unknown health risks against sacred practices.

“We just know that if we overconsume a certain amount of it that it might have possible risks,” Sam said as she gutted salmon in the bustling kitchen. “It’s our food. We don’t see it any other way.”

But while tribes have pushed the government to pay closer attention to contamination, that hasn’t happened. Regulators have done so little testing for toxic chemicals in fish that even public health and environmental agencies admit they don’t have enough information to prioritize cleanup efforts or to fully inform the public about human health risks.

So Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica did our own testing, and we found what public health agencies have not: Native tribes in the Columbia River Basin face a disproportionate risk of toxic exposure through their most important food.

OPB and ProPublica purchased 50 salmon from Native fishermen along the Columbia River and paid to have them tested at a certified lab for 13 metals and two classes of chemicals known to be present in the Columbia. We then showed the results to two state health departments, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials and tribal fisheries scientists.

The testing showed concentrations of two chemicals in the salmon that the EPA and both Oregon and Washington’s health agencies deem unsafe at the levels consumed by many of the 68,000-plus Native people who are members of tribes living in the Columbia River Basin today. Those chemicals are mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, which after prolonged exposure can damage the immune and reproductive systems and lead to neurodevelopmental disorders.

The general population eats so little fish that agencies do not consider it at risk, which means that government protocols are mostly failing to protect tribal health. In fact, the contaminants pose an unacceptable health risk if salmon is consumed even at just over half the rate commonly reported by tribal members today, according to guidelines from the EPA and Washington Department of Health.

Contaminants in Fish Put Tribal Members at Risk

The potential for exposure extends along the West Coast, where hundreds of thousands of people face increased risks of cancer and other health problems just by adhering to the salmon-rich diet their cultures were built upon.

Chinook salmon, like the ones OPB and ProPublica sampled, migrate to sea over the course of their lives, where they pick up contaminants that Northwest waters like the Columbia and other rivers deposit in the ocean. EPA documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act show that even with minimal data available, agency staff members have flagged the potential for exposure to chemicals in salmon caught not just in the Columbia but also Washington’s Puget Sound, British Columbia’s Skeena and Fraser rivers, and California’s Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

Tribes entered into treaties with the U.S. government in the mid-1850s, ceding millions of acres but preserving their perpetual right to their “usual and accustomed” fishing areas; the Supreme Court later likened this right to being as important to Native people as the air they breathe.

But time and again, the U.S. has not upheld those treaties. Damming the Columbia River destroyed tribal fishing grounds and, along with habitat loss and overfishing, drove many salmon populations to near extinction, wiping some out entirely. Previous reporting has shown how the federal government failed in its promises to compensate tribes for those losses and in some cases worked against tribes’ efforts to restore salmon populations. In addition, the EPA has allowed cleanups to languish, and state regulators have been slow to rein in industrial pollution. That toxic pollution impairs the ability of salmon to swim, feed and reproduce.

Continually poor and declining salmon numbers have prompted the White House to acknowledge an environmental justice crisis in the Columbia River Basin.

The results of our testing for toxic chemicals point to yet another failure.

A Toxic Mystery

Questions over fish safety go back generations in some tribal families, predating government concerns by decades.

Karlen Yallup remembers tribal elders telling her the water had been clean enough to drink at Celilo Falls, their primary fishing site on the Columbia River. Yallup’s great-great-grandparents, members of the Warm Springs tribe, lived near the falls and would fish there every day.

As the industrial revolution boomed, farming, industry and urban sprawl grew throughout the basin. In 1957, the falls were submerged by water that pooled behind The Dalles Dam — one of 18 built on the Columbia and its main tributary, the Snake River, to turn the river into a shipping channel, irrigate farmland and generate hydroelectricity. By then, pollution from those new industries had dirtied the water.

Tribal elders told Yallup they knew the water was no longer clean enough to drink when they could see changes and hear differences in the way it ran. They also worried about the health impacts of Hanford, a sprawling nuclear weapons production complex dozens of miles upstream. Hanford became one of dozens of heavily polluted sites across the Columbia basin, considered one of the largest and most expensive toxic cleanups in the world.

Yallup said her elders began to suspect that whatever was getting into the water was getting into the fish. They became “very worried about the salmon getting the family sick,” she said.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, however, that the government and the broader public drew attention to the risk to people eating those fish.

In 1992, despite two decades of improving water quality under the Clean Water Act, an EPA study found chemicals embedded in carp from the Columbia River. The results alarmed the region’s tribes, which responded by working with the agency to test more fish and survey members about their fish consumption rates.

Those efforts revealed that tribal people, on average, eat six to 11 times more fish than non-tribal members. They also detected more than 92 different contaminants in the fish, some at levels high enough to harm human health.

In the years that followed, EPA staff expressed concerns over toxic contamination in report after report, but little happened in response. The issue officially became an agency priority during the administration of President George W. Bush, but the EPA repeatedly fell short of its goals to clean up toxic sites as responsible parties fought over how much it would cost, who would pay and how quickly it needed to be done.

The agency also never had the money to fulfill its plans for continuous monitoring, said Mary Lou Soscia, the Columbia River coordinator for the EPA, leaving the agency unable to determine whether the river was getting cleaner.

“Nobody wanted to pay attention to toxics,” said Soscia, who has been working on river cleanup since the late 1990s. “But there are small amounts of studies that give us like those yellow blinking lights. And when tribal people eat so much fish, it’s something we have to be really, really concerned about.”

Finally, Oregon delivered in 2011 what was hailed as a breakthrough moment: It adopted new water-quality standards to protect tribal people’s health. The state vowed to restrict the amount of chemicals released by industrial facilities and wastewater plants so that people could eat over a third of a pound of fish per day without increasing their risk of health problems. That amount of fish was based on a survey of tribal members done in the 1990s.

Other states that share the Columbia River or its tributaries were slow to follow suit. Washington waited a decade to adopt equally protective standards; Idaho and Montana still have not.

But while Oregon was ahead of its neighbors, state regulators took few steps to ensure polluters actually met the state’s new limits. For as many as half the contaminants at issue, the state said it didn’t have the technology to measure whether polluters met the new stricter criteria.

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality also said it didn’t have the staff to keep pollution permits updated. It let more than 80% of polluters operate with expired permits, meaning they weren’t even being held to new standards.

When asked in September for evidence of how the state’s highly touted standard has actually improved water quality, the DEQ said it “does not have significant amounts of data on the concentration of bioaccumulative pollutants in the Columbia River, and therefore does not have any trend information.”

Jennifer Wigal, DEQ’s water quality administrator, said the standards were implemented not because of pollution but to ensure that tribal diets were represented.

Wigal also said that when companies release harmful contaminants into the river, most are at such low concentrations that they are below the agency’s ability to detect them. Additionally, most of the contamination affecting fish, the DEQ said, comes not from those polluters but from runoff and erosion from industries like agriculture and logging.

But the DEQ also has yet to curtail that source of pollution. Along the Willamette River, which flows through Oregon’s most populated areas and feeds into the Columbia, the EPA determined last year that the state needed to cut mercury pollution from these sources by at least 88% if it was going to meet its standards for protecting human health.

Congress tried to take matters into its own hands, but it fell into the same pattern of bold plans and delayed action. In 2016 it amended the Clean Water Act, the seminal law governing water pollution nationwide, to require the EPA to establish a program dedicated to restoring the Columbia. It took four years and a nudge from the Government Accountability Office for the program to actually begin. That same year, in 2020, an EPA regional staffer found that broad swaths of the river were polluted with toxic chemicals and were below the standards of the Clean Water Act.

In an emailed response to questions, the EPA repeatedly said Congress gave the agency orders to clean up the Columbia but failed to provide the agency with funding to carry out the work. Even after the agency designated the Columbia an EPA priority, finally elevating the river to the same status as other major ecosystems like the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico, it received no additional funding and staff for cleanup or long-term monitoring.

“That needs to happen,” Soscia, the agency’s Columbia River coordinator, said. “It hasn’t happened.”

A Disproportionate Risk

Had the government followed through on its plans for monitoring, it might have found what OPB and ProPublica’s testing revealed: that contamination was high enough that it would warrant at least one of the state health agencies to recommend eating no more than eight 8-ounce servings of salmon in a month.

For non-tribal people, who on average eat less than those eight monthly servings, the risk is minute. But surveys show members of some tribes in the Columbia River Basin on average eat twice as much fish as the agency’s recommended eight monthly servings.

The testing also revealed the potential for increased cancer risks from PCBs and another class of chemicals known as dioxins. Given an average Columbia River tribal diet, according to recent surveys commissioned by the EPA, the risk is as much as five times higher than what the EPA considers sufficiently protective of public health. This means that, based on the news organizations’ samples, roughly 1 of every 20,000 people would be diagnosed with cancer as a result of eating the average tribal diet — about 16 servings of fish each month — over the course of a lifetime.

The harm goes beyond the raw numbers. That’s because the risk is compounded by exposure from other fish and other toxic chemicals, such as pesticides and flame retardants in those same waters, that weren’t included in OPB and ProPublica’s testing because of cost constraints. Those chemicals are known to accumulate in fish. Beyond fish contamination, tribal populations already experience disproportionately high rates of certain cancers.

Public health officials caution that any cancer risks must be weighed against the many health benefits of eating fish, including the potential to lower the risk of heart disease. The Oregon and Washington health departments, like those of many states, do not assess cancer risk when setting public health advisories.

We showed the result of our testing to public health officials in both Washington and Oregon. Both groups said they would be taking further steps to assess salmon and the exposure risk to tribes.

Emerson Christie, a toxicologist with the Washington Department of Health who analyzed the results, said the department will consider whether to issue an official public health advisory based on the news organizations’ findings. “These results do indicate that there’s a potential for a fish advisory,” Christie said.

David Farrer, an Oregon Health Authority toxicologist who also reviewed the results, said the agency would coordinate with state environmental regulators and the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission about additional testing or potential advisories.

Public health advisories and cooking guidance are a last-resort attempt to protect people when larger cleanup efforts fall short or don’t happen at all.

These advisories can also be plagued with delays. When tribes collected and tested tissue from the Pacific lamprey back in 2009, they found that the culturally important eel-like fish contained dangerous levels of mercury and PCBs. The Oregon Health Authority responded by issuing a consumption warning in October — but the process took 13 years.

And while advisories put constraints on tribes’ traditional diets, they don’t help with the larger issue: that the waters from which they are eating fish are still contaminated — with no plan to clean them up.

“The long-term solution to this problem isn’t keeping people from eating contaminated fish — it’s keeping fish from being contaminated in the first place,” Aja DeCoteau, executive director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, said when the lamprey advisory was issued.

Wilbur Slockish Jr. is a longtime fisherman who serves on the inter-tribal fish commission.

It is wrong, Slockish said, for the government to allow pollution and then, instead of cleaning it up, decide it can tell people not to eat the fish they always have.

“That’s on the back of our people’s health, the health of the land, the health of the water,” he said. “We’re not disposable.”

A Fight Too Big to Ignore

Slockish eats a lot of fish.

He relies on stockpiles of jarred, dried or smoked salmon to get him through the winter. He said it’s not uncommon for him to eat more than a pound of salmon or lamprey in one sitting, sometimes multiple times per day.

He’s a direct descendant of the Klickitat tribe’s Chief Sla-kish, who signed the Yakama Treaty of 1855, guaranteeing his people’s right to the fish. At that time, studies estimate that, on average, Native people in the region ate five to 10 times more fish than they do today. Slockish is not going to stop eating fish because of warnings about chemical contamination.

He doesn’t see the alternatives as any better. Many in his family have struggled with heart disease, diabetes and cancer. He connects it to their being forced away from the river and made to eat government-issued commodity foods full of preservatives.

“All of our foods were medicine,” he said. “Because there were no chemicals.”

Research across the globe has connected the loss of traditional diets with spikes in health problems for Indigenous populations. In one West Coast tribe, the Karuk of Northern California, researchers found a direct link between families’ loss of access to salmon and increased prevalence of diabetes and heart disease.

Public health experts agree that wild salmon, wherever it’s caught, remains one of the healthiest sources of protein available, and that chemicals can also contaminate other foods beyond just fish.

Tribal leaders also worry more about their members getting too little fish than too much of it. And because salmon are a primary income source for many tribal fishers, they worry that fears over fish safety will drive away customers.

But for Columbia River tribes, fish are also a cultural fixture, present at every ceremony. They are shared as customary gifts. Babies teethe on lamprey tails. Salmon heads and backbones are boiled into medicinal broths for the sick and elderly.

Tribes up and down the river continue to fight for their right to a traditional diet and to clean fish.

Yallup, from the Warm Springs tribe, decided to become an advocate for salmon after hearing from her grandmothers how much more limited their traditions had become.

She’s on track to graduate in December from Portland’s Lewis & Clark Law School. Yallup chose the law profession to fight for salmon, she said, and to change laws to protect the river from pollution.

“If I had a choice, I would just be a fisherman. I felt the responsibility to have to leave the reservation and have to go to law school,” Yallup said. “It’s such a big fight now. It’s kind of impossible to ignore.”

Earlier this year, tribes successfully lobbied for one of their Columbia River fishing sites just east of Portland, known as Bradford Island, to be added to the list of polluted places eligible for cleanup money from the federal Superfund program.

In August, the EPA received $79 million to reduce toxic pollution in the Columbia River as part of President Joe Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. It is the most money ever dedicated to reducing Columbia River contamination. It’s also a fraction of what tribes and advocates say is needed.

The Yakama Nation is using some of that EPA money to lead a pilot study into the kind of long-term monitoring that has been a recognized need for decades.

Laura Klasner Shira, an environmental engineer for Yakama Nation Fisheries, said the tribe put together four federal grants to pay for its pilot study, which is limited to the area around Bonneville Dam, east of Portland. They hope someday it could grow to span nearly the entire length of the Columbia, up to the Canadian border. But it took 10 years to get as far as they are now.

“It’s disappointing that the tribes have to take on this work,” she said, noting that government agencies not only have treaty and legal responsibilities but better funding. “The tribes have been the strongest advocates with the least resources.”

They will sample resident fish, young salmon on their way to the ocean, and adult salmon after they’ve returned.

They have two years to finish the work. After that, funding for their monitoring becomes a question mark.

Methodology

Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica reporters conducted interviews and listening sessions with tribal leaders, toxicologists and public health experts, many of whom became informal advisers throughout the project. Tribal leaders expressed support and interest in additional fish testing. Based on these conversations, the reporters developed a preliminary methodology to test salmon for toxics in a stretch of the Columbia River. The reporters sent this methodology to the same informal advisers for review.

A reporter purchased 50 salmon from tribal fishers upriver of the Bonneville Dam, in the zone of the river reserved for tribal treaty fishing. The majority of the fish were fall Chinook salmon, with two coho salmon and one steelhead. The fish were caught in late September 2021. With the salmon in hand, a reporter gutted the fish, removed the heads and cut them into pieces so they would fit into five coolers. The fish were placed on ice in five different coolers, with 10 fish of roughly the same size placed in each cooler.

Testing of fish can be done on the whole body of the fish, on a fillet with the skin on or on a fillet with the skin removed. Although many people, particularly in tribal communities, consume the head of the fish, reporters asked the laboratory to test fillets with skin because it was determined to capture the best approximation of what’s most often consumed in tribal diets.

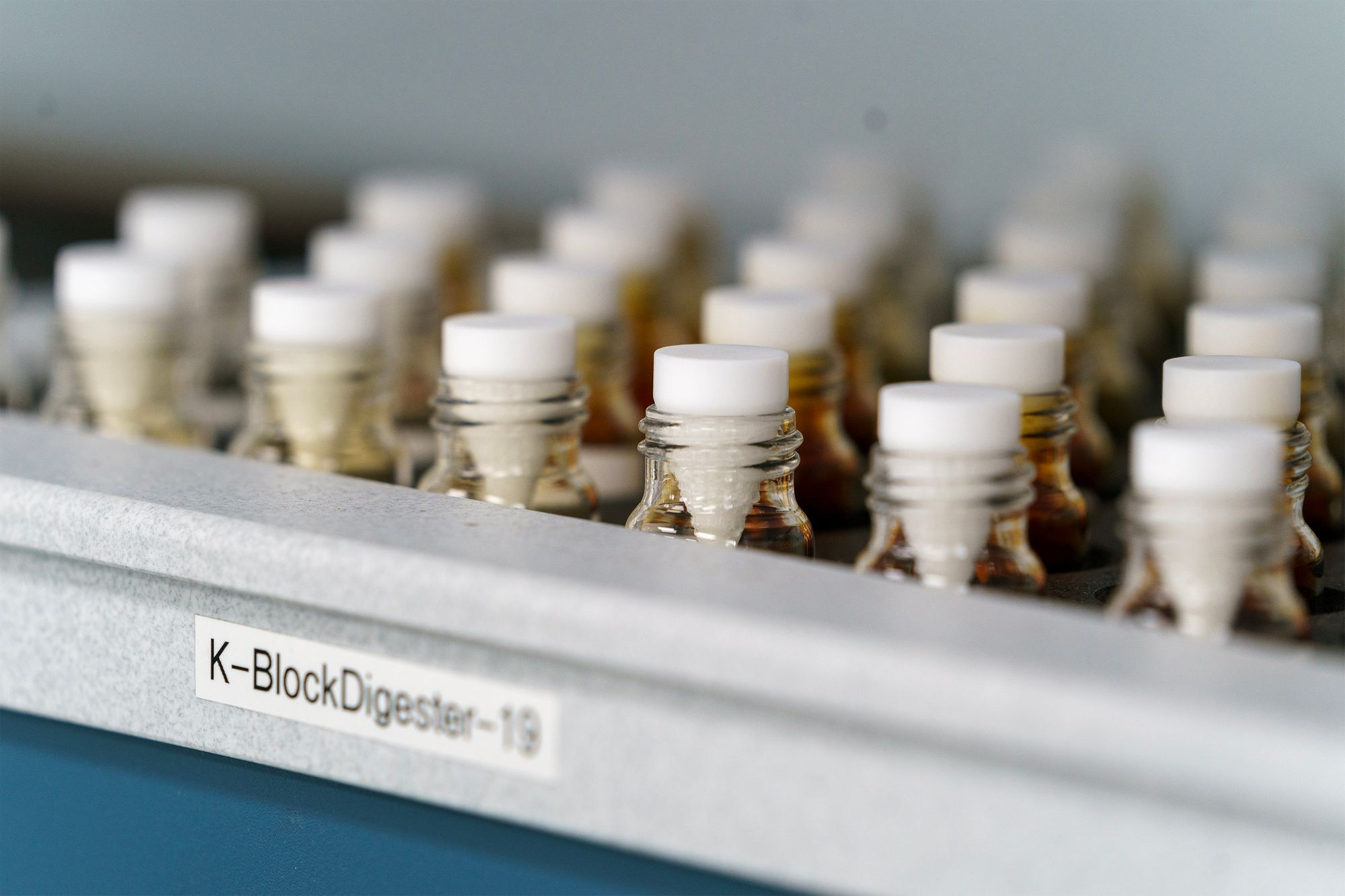

A reporter sent the fish samples to ALS, a certified laboratory, and followed ALS protocols for the collection and delivery of samples. The laboratory combined fish to create five new composite samples, each one with 10 fish. (Creating composite samples enables more fish to be tested without raising laboratory costs.) Then, ALS technicians conducted testing to assess levels of 13 metals and two classes of chemicals in each of the five fish samples. In March 2022, ALS sent OPB and ProPublica an analytical report that included the case narrative, chain of custody and testing results, which we again shared with experts and public health officials as we developed a plan to analyze the results.

As a first step, the reporters conducted quality assurance checks on the testing and processed the data. While doing so, the reporters encountered testing limitations that prompted them to make two choices that are standard in both national and international approaches to fish toxics testing:

ALS tested for general mercury, yet methylmercury is the form that is most concerning to public health. The EPA and European Food Safety Authority assume 100% of mercury sampled in fish tissue is methylmercury. The reporters adopted the same approach.

ALS tested for arsenic, yet inorganic arsenic is the form that is most concerning to public health. The reporters found that there isn’t as much of a cohesive approach toward identifying the proportion of arsenic that is inorganic without directly testing for it. The Idaho Department of Environmental Quality recently launched a sampling effort where researchers found that, on average, about 4% of the arsenic in fish is inorganic. The department’s study is one of the most robust examinations of inorganic arsenic concentrations near the Columbia River. The Oregon Health Authority takes a different approach. David Farrer, a toxicologist with the agency, said they would initially assume 10% of arsenic is inorganic and, if the results signaled the levels could harm human health, they would then reanalyze any leftover sample specifically for inorganic arsenic. If that were not possible, the health department would not use the data at all. Given these uncertainties, OPB and ProPublica chose not to move forward with assessing cancer risk of inorganic arsenic since the news organizations did not specifically test for it.

The reporters then calculated the average concentration of chemicals across each of the wet weight samples. They then assessed how these results compared to EPA, Oregon Health Authority and Washington Department of Health standards.

Of the 13 metals and two classes of chemicals tested, three contaminants surpassed federal and local standards at varying levels of fish consumption: mercury, or methylmercury; polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs; and dioxins/furans.

The reporters shared their methodology and findings with experts for review. Toxicologists with the Oregon Health Authority and the Washington Department of Health, as well as former and current EPA scientists, reviewed the results and, in some cases, conducted their own calculations to assess how the testing findings compared to their respective standards. The reporters then met with each of these individuals to talk through the findings, ask and answer questions, and ultimately update their own findings to incorporate feedback. The experts’ feedback was consistent with one another. This process led to the finding that concentrations of mercury (methylmercury) and PCBs would warrant the EPA and at least one state health agency to recommend eating no more than eight 8-ounce servings of salmon in a month. The equation used for these calculations can be found in this Oregon Health Authority report (Page 4) and this Washington Department of Health report (Page 35).

Simultaneously, OPB and ProPublica calculated the estimated cancer risk from consuming salmon with the contaminant levels found through our testing. For each contaminant, a reporter calculated the levels of exposure for multiple scenarios based on how different populations eat, including general population consumption and average and high rates for Columbia River tribes, which were based on consumption surveys. The amount of contamination assumed in this calculation was taken from the 95% upper confidence limit of the test results. Current and former EPA scientists reviewed the methodology and calculations.

To calculate lifetime cancer risk, the dose of a probable carcinogen must be multiplied by a cancer potency factor, which estimates toxicity. Cancer potency factors, also known as slope factors, were sourced from this EPA report. Former and current EPA officials, as well as an epidemiologist, reviewed the calculations and results.

We also factored in the following consideration: Under EPA guidance, when calculating safe levels of exposure to different chemicals, the agency calculates monthly limits to the exact number of meals a person should eat. But it then rounds that down to the nearest multiple of four in an effort to make risk communication easier to follow. For example, if one were to find that the levels of dioxins would warrant that someone only eat five fish per month to avoid excess cancer risks, that would be rounded down to the four fish per month.

Ultimately, this led to the finding that, based on the levels of dioxins in our samples, anything above four 8-ounce servings of these tested fish each month would create an excess cancer risk beyond the EPA’s benchmark of 1 in 100,000. That means of 100,000 people exposed to these levels of contaminants, one of them would develop cancer as a result of the exposure.