When a US federal agency approved the largest dam removal project in US history late last year, Yurok tribe chairman Joseph James praised the many people who had sought environmental justice for Klamath River communities: ‘The Klamath salmon are coming home.’ Nearly a year later, work to take out the first of the dams scheduled for removal – Copco No. 2, the smallest – is now complete, restoring flows to the Klamath river canyon for the first time in 98 years.

Between 1908 and 1962, four hydroelectric dams were built along a 645-kilometre stretch of the Klamath, where the river crosses the border between Oregon and California. For 20 years, communities and conservationists have fought for their removal, citing dramatic declines in fish populations, the knock-on effect for local fisheries and public safety concerns over water quality – in particular, the huge toxic algal blooms in the dam reservoirs. On 17 November, after six years of negotiations, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued the final approval for their decommissioning. It’s a decision that could mark a turning point in the future of thousands more dams across the country.

The movement to restore rivers to their free-flowing state is gaining traction – 2021 was a record-breaking year for dam removals across Europe; 17 countries decommissioned a total of 239 dams. The USA removed 57 dams in the same year, freeing nearly 3,500 kilometres of river. According to American Rivers, nationwide, more than 1,950 dams have now gone, 76 per cent of which were removed in the last two decades.

Many of these US dam removals were precipitated by the expiry of operating licences, typically issued for 40–50 years. Adell Amos, an environmental law professor at the University of Oregon with extensive knowledge of the Klamath Basin, explains that when that happens, the conditions for renewal often require owners to address dam impacts to the environment and to the water rights of local Indigenous nations, as well as any safety and maintenance issues. This relicensing process has become a powerful tool for re-evaluating whether the benefits of maintaining a dam outweigh the costs. In the case of the Klamath River, ‘it became clear that the economics of these facilities no longer made much sense’.

Even without the renewal process, however, the Klamath dams were likely to have been decommissioned. Many US rivers are subject to complex water rights, but Amos says that she could teach her whole water law course syllabus just using examples from the Klamath. Power companies, farmers, fisheries, tourism businesses and a handful of Indigenous tribes, as well as species such as the Coho salmon, are just some of the different parties that depend on the river. ‘The level of conflict caused by competing water rights, and the level of demand on that one water source, meant that something had to give. There’s just not enough water in the system.’

While removing the dams won’t change the volume of water in the river, it will improve its quality, increase the amount of fish habitat and make the Klamath more resilient to changing climate conditions and the droughts that have plagued the river basin. Amos describes the decision to decommission, which begins this year, as a ‘really significant moment’. With a combined height of 125 metres, roughly the height of the Great Pyramid of Giza, it will be ‘no small feat of engineering to get those structures out.’

Dam removals result in fundamental changes to the local environment and there are risks involved on any scale. ‘The sediment held behind dams is usually highly contaminated by heavy metals, industrial chemicals, fertilisers and other pollutants,’ says Upmanu Lall, director of the Columbia Water Centre. ‘If you release them, it could be deleterious to river ecosystems and other water users, so removals have to be done right.’ The removal work, environmental risk assessments and ongoing work to restore river ecosystems all make dam decommissioning expensive; US$450 million of funding has been allocated for the Klamath River Renewal Project.

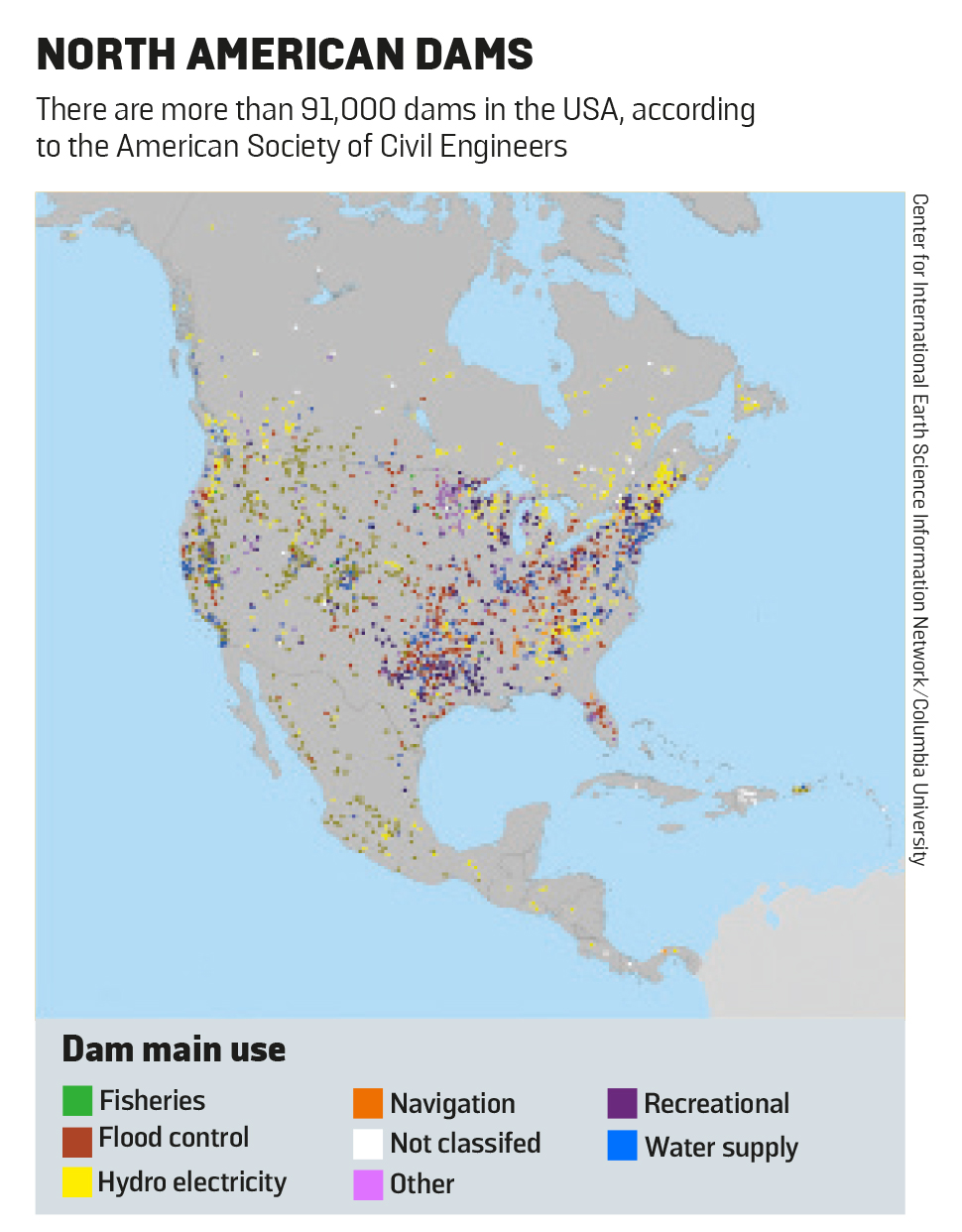

Despite this, Amos thinks we will see a lot more US dams being decommissioned in the future, even as countries in Africa, Asia and South America are experiencing a continued increase in the number of dams currently planned or under construction. The biggest reason is that most US dams are now quite old. ‘We have 92,000 dams in the USA,’ says Lall. ‘Their median age is around 57 years; their design lifespan is 50 years. The state of maintenance of many of them is highly unclear.’

The ageing Klamath hydroelectric dams generate very little energy even when running at full capacity, which doesn’t happen much due to low water levels. For the Klamath tribes, their removal equates to food security, health and cultural survival. ‘There’s a juxtaposition between the need to decarbonise the energy sector and the role that hydropower can play in that,’ says Amos, ‘and the reality is that so many of these facilities aren’t particularly significant in terms of their carbon-reduction capacity, and are harmful to ecological and Indigenous rights.’