A company with ties to oil shale development in western Colorado has dropped its attempt to maintain water rights for a proposed reservoir on Thompson Creek.

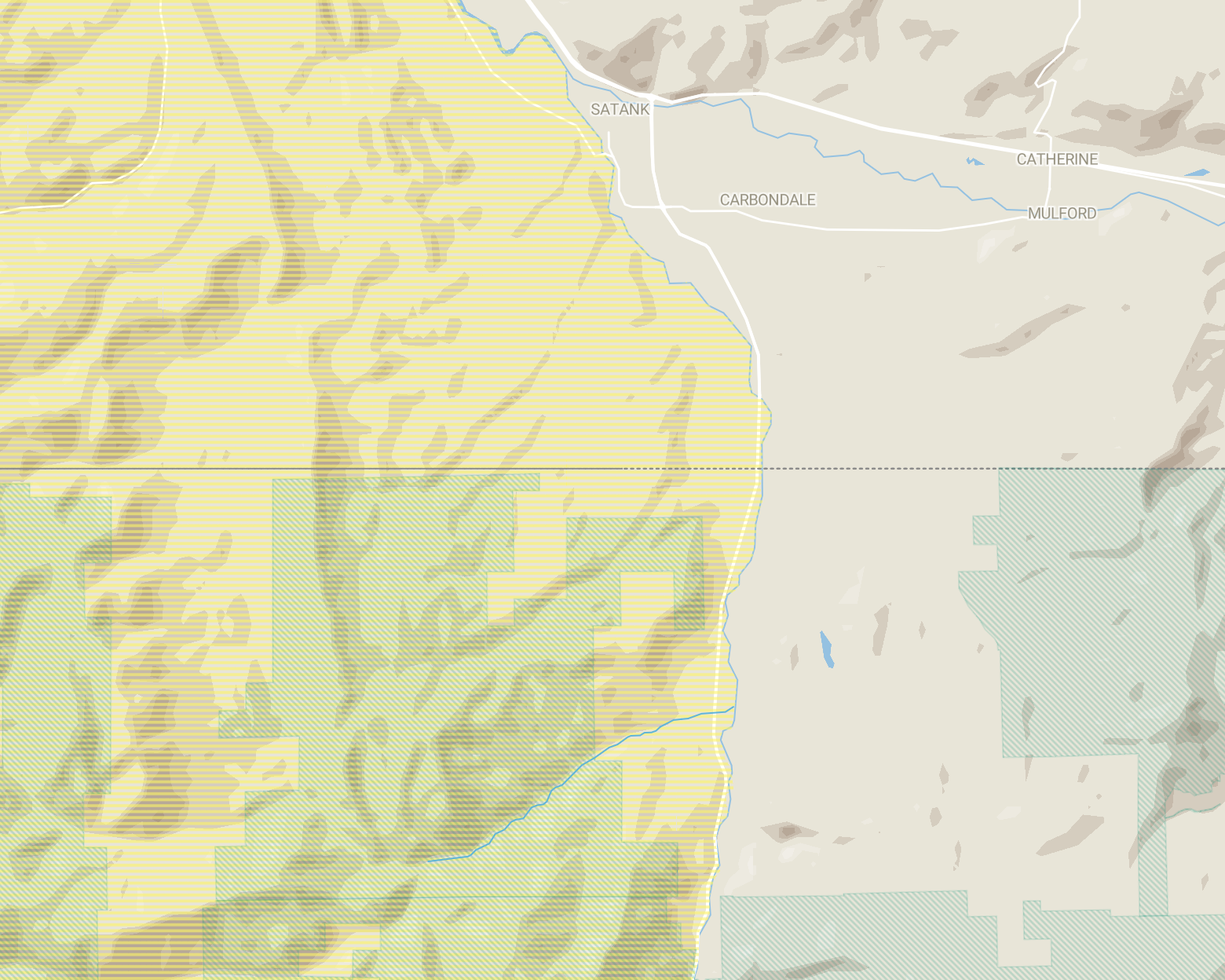

Puckett Land Co. on Jan. 26 filed a motion to dismiss its diligence application for conditional water rights that date to 1966 and are associated with the construction of a 23,983-acre-foot reservoir on Thompson Creek, a tributary of the Crystal River just south of Carbondale. Later that day, a water court judge signed off on the motion, meaning the water rights have now been abandoned.

The Greenwood Village-based company holds interests in 17,500 acres of land in Garfield and Rio Blanco counties, according to its water court filing. Attorney for Puckett Megan Christensen said the decision to voluntarily cancel these water rights was for business purposes. In its November filing, known as a diligence application, Puckett had said that current economic conditions are adverse to oil shale production.

“Puckett has a portfolio of water rights and in looking at them, they made the decision that this one wasn’t worth maintaining anymore, so they decided to just go ahead and dismiss it,” Christensen said in an interview with Aspen Journalism.

The proposed reservoir site had been on BLM land in Pitkin County within the boundaries of an area that the U.S. Forest Service and BLM are proposing to withdraw from eligibility for new oil and gas leases. The proposed Thompson Divide withdrawal area is comprised of 224,713-acres in Garfield, Gunnison and Pitkin counties that generally straddles the ridge of mountains running from south of Glenwood Springs to the northern edge of the West Elk Wilderness, south of McClure Pass.

Carbondale conservation group Wilderness Workshop supports the withdrawal area and celebrated Puckett dropping the water rights as a win for the Crystal River.

“This is great news for the Thompson Divide, the Crystal River, and our local ecosystem and communities,” Will Roush, executive director of Wilderness Workshop, said in a prepared statement. “Puckett’s intention to cancel their conditional water rights demonstrates just how speculative conditional water rights associated with oil shale development are. Other holders of similar rights ought to follow Puckett’s lead.”

Proposed Thompson Creek reservoir

Conditional water rights

Puckett is among the companies with an interest in western Colorado oil shale development, who have water rights dating to the 1950s and ‘60s, which were amassed in anticipation of a boom. A report produced by conservation group Western Resource Advocates in 2009 found that there were conditional water rights associated with oil shale development for 27 reservoirs with 736,770 acre-feet of water in the mainstem of the Colorado River basin.

Companies have been able to hang onto these conditional water rights in some cases for over 50 years without using them because Colorado water law allows a would-be water user to reserve their place in the priority system based on when they applied for the right — not when they put water to use — while they work toward developing the water. Under the cornerstone of water law known as prior appropriation, older waters rights get first use of the river.

To maintain a conditional right, an applicant must every six years file what’s known as a diligence application with the water court, proving that they still have a need for the water, that they have taken substantial steps toward putting the water to use and that they “can and will” eventually use the water. They must essentially prove they are not speculating and hoarding water rights they won’t soon use.

But the bar for proving diligence is low. Judges are hesitant to abandon these conditional water rights, even if they have been languishing without being used for decades.

Before Puckett dropped its diligence application, John Cyran, senior staff attorney for Western Resource Advocates’ Healthy Rivers Program, said holding onto conditional rights like these raised speculation concerns.

“The water is being held without a plan to use it, which violates a central tenet in western water law,” Cyran said in an email.

“Water shortages are affecting Colorado’s communities, fish and wildlife. We cannot afford to let companies profit off these shortages by holding onto unused conditional water rights.”

Crystal River Ranch was the only entity to file a statement of opposition to Puckett’s application. The deadline to file a statement of opposition is Jan. 31.

Crystal River Ranch also expressed concern that the over-50-year-old water rights had never been used and said that over the five decades Puckett had not shown it would develop them.

“During that period, the applicant has failed to obtain the necessary federal, state and local permits required to develop this reservoir,” the statement of opposition reads. “Therefore, this subject conditional water right must be canceled and abandoned.”

The Thompson Creek water rights had been part of a proposed “integrated system” that includes conditional water rights for two proposed small reservoirs, and a pump and pipeline on Starkey Gulch, a tributary of Parachute Creek. The application did not specifically mention work regarding the Thompson Creek reservoir site in its list of diligence activities and Puckett had said that diligence on any part of the system constitutes diligence with respect to the entire system. It is unclear how the Thompson Creek reservoir would have operated with these other parts of the system, but Christensen alluded to the reservoir being conceived of as additional back-up supply.

Christensen said the water rights applications for the Starkey Gulch components are still going forward because those water rights are closer to Puckett’s landholdings. These diligence applications were filed on Nov. 30 and so far no entities have filed statements of opposition.