As a wave of wealth sweeps Montana, landowners are blocking the public from public lands.

We had followed the trail for a half mile when it ran headlong into a fence.

Signs nailed to the trees blared messages of unwelcome: “Private Property” and “No Forest Service Access.” They were emphatic: The trail ends here.

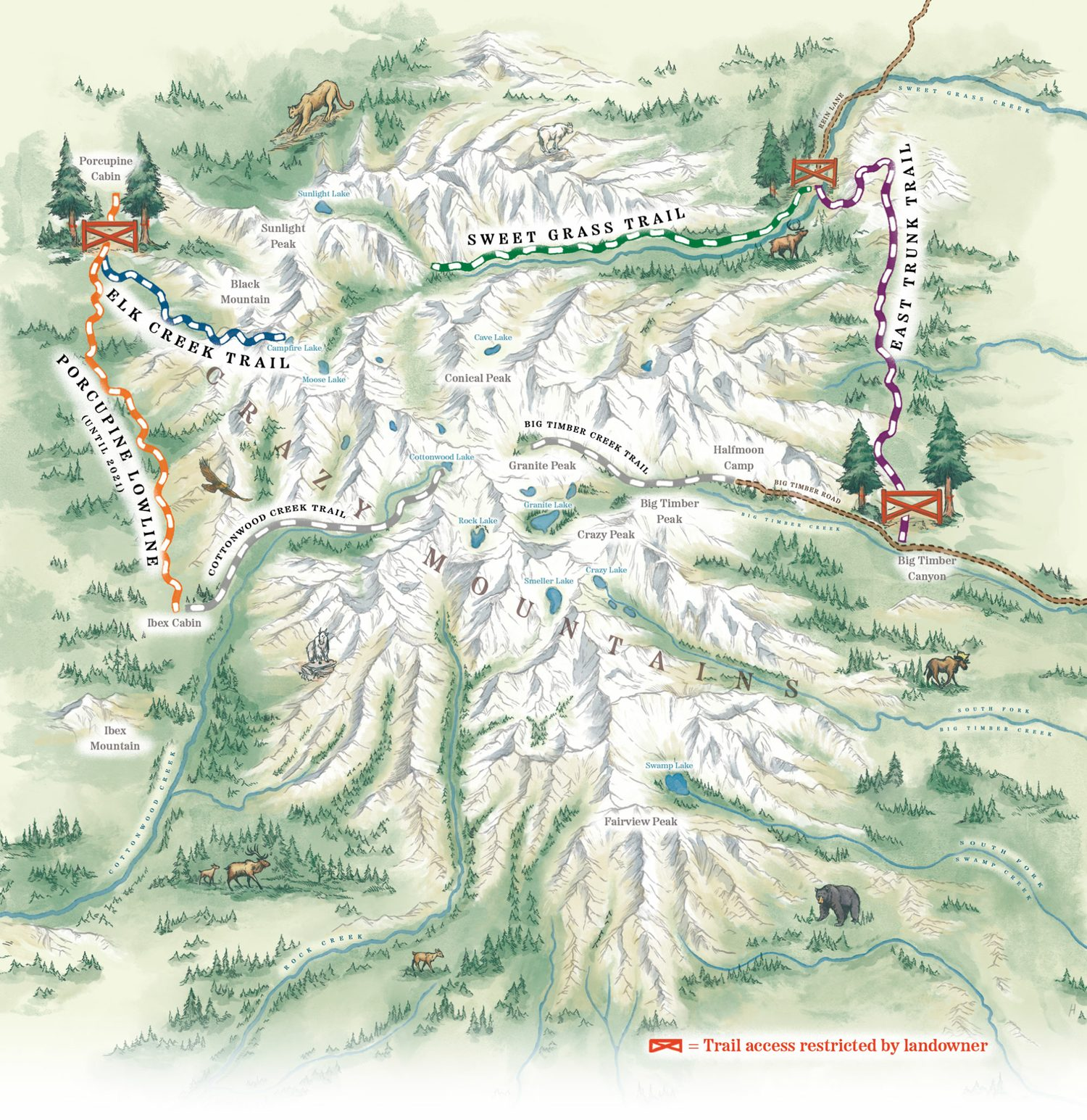

Our map — the official map of the Custer Gallatin National Forest — said different: The trail continued for another seven or eight miles, a substantial orange line winding through the foothills of Montana’s Crazy Mountains.

The signs, though, had the desired effect. On the other side of the fence, the trail grew faint.

This trail, known as the Porcupine Lowline, had been marked on U.S. Forest Service maps for nearly a century — the earliest I’ve seen is dated 1925. But, like many trails in the Crazies, it crossed private land to reach the National Forest. And, like many trails here, landowners had taken to putting up “No Trespassing” signs, fences and padlocked gates at those crossing points. The practice is so widespread that the Forest Service counts only one remaining public access point along the Crazy Mountains’ entire 16-mile southeastern flank.

Practically speaking, this means private landowners have made it much more difficult for the public to access more than 22,000 acres of Custer Gallatin National Forest land.

Which is why I was there that day, in October 2018, with two friends, all three of us reporters at the local newspaper. I wanted to understand the disputed trails by walking them.

We crossed the fence with little ceremony and followed the trail past the signs and into the tree shadows beyond.

These mountains haven’t always felt like hostile territory. At an hour’s drive south of my hometown of White Sulphur Springs, Mont., the Crazies were one of our backyard ranges, though steeper, wilder and stranger than the others. My family often camped here, and through my teenage years, my dad, my younger brother and I took a week most summers to disappear into the high Crazies. We’d strap packs across our bony backs, stagger several miles into the mountains, and make camp in our favorite spot: a high-altitude meadow of flowers and grouse whortleberries blooming lush and absurd between snowfield and scree. A trickle of snowmelt cuts a groove through this carpet of greenery, and altitude-stunted hedges of spruce and whitebark pine offer firewood. Looming over it all, a massive cone of raw diorite: Crazy Peak, 11,214 feet tall, the highest point in the range.

My family, it turns out, has a rich tradition of trespassing. The meadow where we camped and Crazy Peak itself, I’ve since learned, were owned by a local ranch. While most of the Crazies are public land managed by the Forest Service, they are checkered with these square-mile sections of private land. That’s because, in an 1864 land grant to subsidize construction of transcontinental railways and promote colonization of the West, the U.S. government transferred every other section in the Crazies and elsewhere to the Northern Pacific Railway, up to 20 sections for every mile of track the company built. This created the checkerboard ownership pattern that troubles maps to this day. (This land wasn’t exactly the government’s to offer up: Four more years would pass before the Crow Nation officially ceded the Crazies to the United States.)

If my dad knew this was private land — and I doubt he did— he kept it to himself. So did the owners, back then: As we explored the Crazies, we never met a “No Trespassing” sign or a locked gate. Although it’s hard to explain it to newcomers, this was the prevailing culture at the time: You could generally walk in the mountains without worrying whose land you were on, and if you wanted to hunt on private land, you could call or stop by the house for permission.

In the years after my dad died in 2013, I returned to the Crazies often to camp, fish, cut firewood, pick berries, hunt elk, fall down snowfields, limp home. I no longer took the Crazies for granted. Here was land where otherwise landless people could go without having to pay or grovel permission from some capricious baron. Here they could stock up their woodpiles and freezers, take their kids camping, shamble about studying the plants, or just build a big fire and drink beer with friends. These places are the bedrock of a proletarian rural culture that values subsistence, independence and living close to the land.

I also saw that the Crazies were rapidly changing. A great many inholdings, including Crazy Peak and the meadows below it, had recently been sold to Switchback Ranch LLC, owned by billionaire private equity investor David Leuschen. And the company had plans for this property. One day, I followed a helicopter to a cabin construction site by an alpine lake on one of the company’s inholdings, 8,000 feet up and miles from a road. The area bristled with fresh “No Trespassing” signs.

Meanwhile, down in the foothills, other landowners were choking off public access routes and effectively privatizing vast swaths of the mountains.

What was going on here?

The Crazies, it seems, have been swept up in the wave of wealth and gentrification that is reshaping the West — driving up housing costs in nearby towns, displacing working-class residents and carving up the landscape for profit. Among the newcomers to the Crazies is CrossHarbor Capital Partners, which owns the Yellowstone Club, an ultra-exclusive residential development near Big Sky that boasts the only private ski and golf resort in the world and where membership costs millions of dollars. In 2021, CrossHarbor bought (through one of its subsidiary companies) the 18,000-acre Crazy Mountain Ranch and later announced plans for two golf courses. “As incredible a setting [as] there will ever be for the game of golf,” says the website. The company plans to run the ranch as “a private membership experience.”

The real money in the New West is found less in mining, logging and ranching than in selling such exclusive wilderness experiences: remote luxury “cabins,” fly fishing tours, guided hunts for trophy elk, mountain biking and (apparently) golf. But in Montana — where about 35% of the land, most of the mountains and all of the rivers and wildlife belong to the public — creating exclusive experiences often depends on exclusion.

Brad Wilson has watched with growing frustration as “No Trespassing” signs have overrun the Crazies. His family homesteaded here in the 1870s, and Wilson, pushing 70 now, has spent a lifetime exploring these mountains on foot and horseback. His grandfather sold the family place in the 1960s, and Wilson joined that particularly Western class of people with ranch skills but no ranch — and little prospect of ever being able to buy one. So he cowboyed, did a stint as a deputy sheriff, worked as an equipment operator for the county.

“Most of us folks who’ve lived here all our lives, we have eked out a mere existence here,” Wilson says. “We could have went anywhere else and made a hell of a lot more money, but I chose to live here for specific reasons.” Those reasons have to do with the land. “These mountains always drew me back here ’cause I felt free here,” he says.

Maybe the money wasn’t good, but you didn’t need money to backpack with your wife to Campfire Lake in early summer, when clots of white wool adorn the bushes from mountain goats rubbing off their winter coats. You didn’t need money to walk miles of uncrowded trail, where you might pass other locals but also people out for the weekend from Bozeman or Billings (or even Baltimore or Bucharest — the public lands of the Crazies are free to anyone who can get there). You didn’t need money, or much of it, to stack up a good woodpile or put an elk or two in the freezer: A firewood permit on the National Forest costs a few dollars, an elk license costs $20.

But as hunting becomes big business in the West, a license only gets you so far. When I talked to Wilson recently, he’d been calling around looking for a place a friend of his could hunt, but landowners kept giving him the same answer: No, we’ve got the hunting rights leased to an outfitter.

In Montana, as across the United States, wild animals like elk legally “belong” not to property owners but to the public at large. However, landowners can turn a profit from these creatures by charging “trespass fees” for hunting access to or through their property, or by selling guided hunts, which can cost thousands of dollars.

There is plenty of public land in the Crazies where you can hunt for free. Trouble is, because of blocked access, you increasingly can’t get to it, and what you can get to has more hunters on it and less elk. Many low-lying sections of public land here are — because of the land-grant checkerboard— islands surrounded by private land, accessible only by way of these disputed lowline trails. In other cases, the blocked trails just make access harder, sometimes much harder.

Wilson founded Friends of the Crazy Mountains (a group that advocates for public access here) after landowner Ned Zimmerman fenced off the Porcupine Lowline — and so blocked Wilson from the shortest route to, among other places, Campfire Lake. The same is true of public lands along Sweet Grass Creek, a main drainage on the range’s east side. Because landowners control access, the public can reach the area only by begging permission or undertaking a grueling 10- or 20-mile trek from the other side of the range.

In short, by blocking accesses, landowners can reduce or eliminate the public from these public lands and can in turn provide exclusive access for themselves and their paying customers.

Take, for example, the Rein Anchor Ranch, one of the landowners that controls access up Sweet Grass Creek. Chuck Rein, former president of the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association, also happens to hold an outfitting permit to guide hunts on the National Forest lands accessed by Sweet Grass Trail. The Reins offer a menu of hunts that includes elk ($5,550), elk and mule deer ($7,400) and mountain goat ($5,500). Reached by phone, the Rein Anchor Ranch declined to be interviewed for this story.