Editor’s note: This fourth and final installment of “Aspen: The Embattled Community,” a subset of the “In search of community” series from Paul Andersen and Aspen Journalism, spans 70 years of vision, debate and soul-searching conflicts. Read the rest of the series here.

“Aspen is caught between two competing triads: The Platonic — representing the good, the true and the beautiful; and the Machiavellian — representing money, fame and power.” — Mortimer Adler, resident philosopher of the Aspen Institute

When Elizabeth Paepcke (1902-1994), in her final years, reflected on the Aspen of her dreams and the utopian visions of her husband, Walter, she foreshadowed in a speech to the Aspen Institute a decadeslong outpouring of sorrow over something sacred and ethereal that she felt had been made profane.

“A good deal of courage, imagination and shared guts was needed to do such a thing in a sleepy, almost dead little town in the high Rockies,” she said. “The goal was to make something better than what was begun. My sorrow now lies in the fact that people have come to Aspen to make money. My heart is broken.”

Paepcke spoke from the experience of a past heartbreak when a woodland idyll she had created as a child was desecrated by her insensitive, vandalistic brother. Her lament for Aspen evinced yet another ideal dashed to ruins.

Aspen scribe Peggy Clifford felt Paepcke’s pain for the demeaning of something precious, unique and intangible: “Aspen is more than the sum of its parts,” Clifford wrote in “To Aspen and Back” (1980), her memoir about Aspen in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. “Aspen is an idea.”

Today, many who find themselves in the grips of sentimental loss for a venerated past express similar laments almost daily in paeans to the local newspapers. The gradual and inevitable erosion of familiar people and places in Aspen reflects a community faced with irrevocable and often irreconcilable change.

The most-recent expressions of grief have decried the renaming of the Benedict Music Tent in exchange for a $17 million donation to the Aspen Music Festival and School, monetizing a sacred institution. Another lament mourns the renaming of Pandora’s on Aspen Mountain, where lift-served skiing has made bump runs out of cherished sidecountry chutes.

To many, Aspen appears to be a commodity open to the highest bidder, a place where everything is for sale, where namesake properties are bought and sold as on a Monopoly board, where marketers, real estate agents, appraisers, speculators, bankers and economists are castigated for knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing.

In Aspen today, community members gather for wakes and memorials where they feel a disappearing community bond. Aspen churches and schools remain bastions of community for parents and their children, even though few of those children will have the option to buy in and live in Aspen as working adults. Affordable worker housing in Aspen has enormous demand, and lotteries offer the chance that winners may live in a worker enclave rather than integrating the social strata with what community planners have long referred to as “messy vitality.”

It used to be that ZG license plates, 81612 and 81611 ZIP codes, the 925 telephone prefix and the 7,908-foot elevation identified true locals. Now, it’s an address in Woody Creek, Basalt, El Jebel, Missouri Heights, Blue Lake, Carbondale and beyond. Author Saul Bellow, who spent time in Aspen as a visitor in the 1960s, and witnessed gentrifying trends, suggested that Aspen risked becoming a “pleasure slum.”

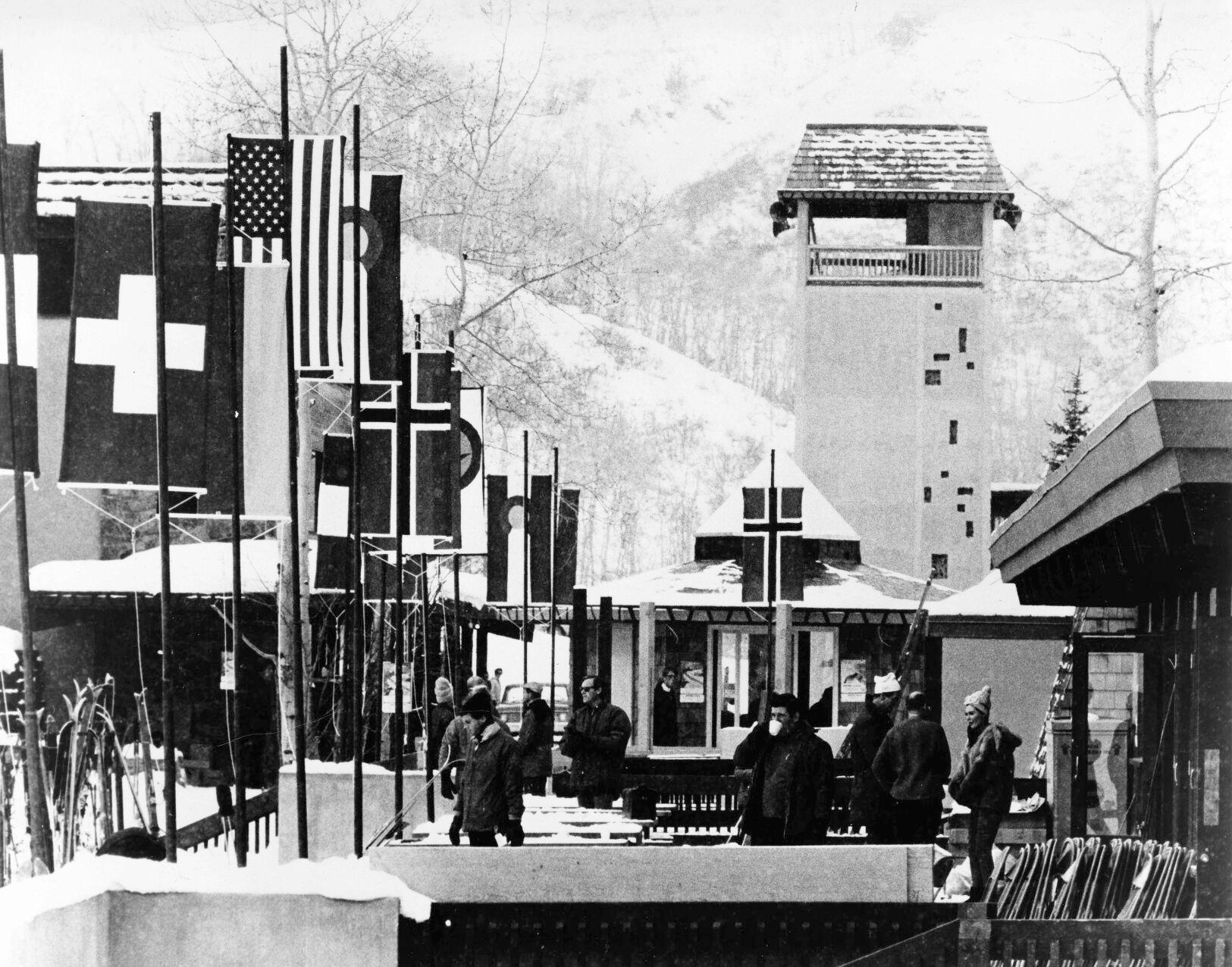

Welcome to the kulturstaat

Paepcke had found elation in the potential for Aspen to thrive under a magical spell manifested by her husband’s original vision of an idealized “kulturstaat,” or culture state, a “high-minded” community that would honor and protect what nature and historical circumstance had wondrously preserved from the mining era.

“Here in the heart of the most materialistic nation in the history of humankind,” Clifford romanticized, “was a town so bent on responding in another way to the imperatives of the times that it built its economy on classical music, scholarly debates and snow.”

During the brief 15 years of his influence here, Walter Paepcke had become a kind of gatekeeper who vowed to keep the rabble at bay in deference to a lofty, intellectual, nonmaterialistic lifestyle. Part of that formula required exclusivity, as Paepcke and friends displayed at the Four Seasons Club in the 1950s.

Hal Rothman, in his 1998 book “Devil’s Bargains,” described “a private club for Paepcke’s associates with plans to designate private fishing rights along Castle Creek and infuse the club with an elitist, urbane overlay that burned locals with resentment.”

Rothman might have been writing about contemporary Aspen’s exclusivity when he characterized Paepcke’s vision for Aspen. Rather than lionize the Chicago industrialist, Rothman described the unintended consequences of a kulturstaat where “Paepcke’s friends and associates began the trend of building luxury second homes, changing the topography and demography of the town incrementally.”

Paepcke’s ambition to make Aspen “a center for understanding and ideas and of transmitting values and meaning in a rapidly changing time,” wrote Rothman, was synchronistic with a national, societal shift. “Paepcke’s experiment in idiosyncratic enlightened capitalism proved to be a pivotal moment in the evolution of tourism in the 20th-century West, a bridge between a more elitist past and a future of mass culture.”

By 1959, reported Rothman, more than 200 second-home owners were added to the community’s 1,800 full-time residents. In Aspen today, 45% of the city’s housing stock, tabulated in a 2021 report as over 2,600 units, consists of units not occupied by a resident. “Aspen acquired a year-round economy and the associated activities that would only grow over time,” wrote Rothman. “Meanwhile, Aspen had a ripple effect on Basalt, where vacationing fishermen began coveting river frontage and parceling out the prime holes.”

The downvalley ripple of Aspen’s regional influence became pronounced in the 1960s when a group of Aspen vigilantes took chainsaws to highway billboards they deemed obnoxious blights on the rural landscape. Others sought to protect the upper Roaring Fork Valley through legislative action.

In 1955, Aspen’s first zoning ordinance was passed to address the rising demand for development: Tourist accommodations could be built only in areas where such facilities already existed; construction in Aspen’s West End had to be on lots equally spacious to the large lots there; and businesses were restricted to the four-block historic business district. These rudimentary guidelines moved Aspen toward what has become one of the most costly places to build, with one of the most restrictive land-use codes, in the United States.

When Aspen ‘split wide open’

In 1960, Walter Paepcke was fatally stricken with bone and lung cancer. Aspen’s thought leader and cultural icon died April 13, 1960, at age 61. “When Arco oilman R.O. Anderson assumed the [Aspen] Institute’s leadership,” wrote Rothman, “Paepcke’s hegemony was all but removed, as was the sway he had held with Aspen old-timers who were gradually voted out of offices they and their forebears had held since the mining years. Aspen lost part of its rudder, and politics became competitive and contentious.”

“The place split wide open,” Clifford wrote of Aspen in the 1960s. “A kind of anarchy surfaced. It had become a free-for-all. Fundamental questions had been left unraised and left unanswered. Nothing was guiding Aspen now but its own momentum.”

That momentum was largely driven by what Rothman described as “neonatives,” a new and often-transitory breed of “locals” who laid claim to Aspen. Young people had “all come to look for America,” as Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel harmonized, and Aspen became hallowed ground in that generational search.

When Clifford arrived in Aspen in the early 1960s, she befriended Fred Glidden, an Aspen writer of Western novels whose pen name was Luke Short. “You will like Aspen,” Glidden told Clifford. “It is a fine, quirky place. There are people here who are straight out of Fitzgerald — golden people whose appetites are as extraordinary as their charms. They play hard and work hard and have no conventional ambitions.”

Clifford described a unique place and time in what seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime alignment of the planets: “We were a special and consecrated breed inhabiting the best of all possible worlds, unspoiled by excess, spacious, open and tranquil. We wore our voluntary poverty like a medal and boasted of our moral superiority.”

Aspen’s isolation, natural beauty and lack of pretension provided fertile ground for the counterculture movement of the 1960s and ’70s, when a surging flood of American youths broke from the mainstream and defined a liberal lifestyle like none before. “People look at Aspen as a refuge,” said one resident in 1970, “a place where you can live the way you want to live, do your own thing in a creative way, and it’s accepted.”

However, a core of Aspen’s old guard was not at all accepting. They derided the hip, young intruders who invaded their so-called paradise. Guido Meyer, Aspen’s magistrate, became consumed by a personal vendetta against hippies, and he dispensed a punitive form of justice upon those whom he considered threats to the decency of his community of friends and neighbors. A selection of Guido’s quotes, published by Aspen Illustrated News, a precursor to the Aspen Daily News, revealed the unmasked hostility of Aspen’s foremost police authority:

– “Beatniks, hippies, they all have long hair. That’s how I can tell them. I prefer dogs to hippies. Dogs are cleaner and have more manners.”

– “Hippies are supported by communists. They are working from within. It’s the same as the Third Column in the ‘30s that gave rise to Hitler.”

– “Riots, hippies, beatniks. They are all the same; working from Moscow. Lawlessness and disorder will be our downfall.”

– “We have gotten too weak. We are not tough like we were in the old days when we took care of the cattle thieves.”

Nonetheless, a revolution was underway in Aspen that shattered the community solidarity that had marked the Quiet Years. A young Aspen attorney named Joe Edwards, who would later profoundly influence Aspen as a county commissioner, took Guido and his minions to task by challenging his dictates based on the contemporaneous groundswell of the civil rights movement. The “hippie trials” provided a successful crusade that would eventually expel the old guard and replace it with a new and ambitious generation of local leaders who took Aspen into a more enlightened era.

Around this time, Aspen’s first master plan — the Aspen Area General Plan — was created in 1966. The plan — initiated by Bauhaus designer Herbert Bayer, 10th Mountain Division veteran and architect Fritz Benedict, and Glidden — would manage rapid growth as seen during the previous decade when, between 1950 and 1960, Aspen’s population increased 44.7%. Another, even-larger jump occurred between 1960 and 1970, when Aspen’s population exploded 158%.

At the time of the master plan, Aspen’s population was 2,300, with another 1,000 outlying in rural Pitkin County, plus accommodations for 6,000 visitors. The plan’s stated purpose was “to retain the fine balance between man and his environment, the essence of Aspen’s character.” Among recommendations was a light-rail system between Aspen and Snowmass, which would later be sidetracked by four-laning Highway 82, a contentious issue that fostered a decadeslong debate.

“The master plan became our bible, our Declaration of Independence,” extolled Clifford. “The rebels liked it because it ensured controlled growth. The burghers liked it because it ensured orderly growth — the sort that affluent America would approve of, the sort that would keep the rabble out and keep prices up.” Clifford, who would flee Aspen after her passionate love affair with the town and community, later noted a telltale advertisement in The New York Times: “Aspen is a party and you’re invited.”

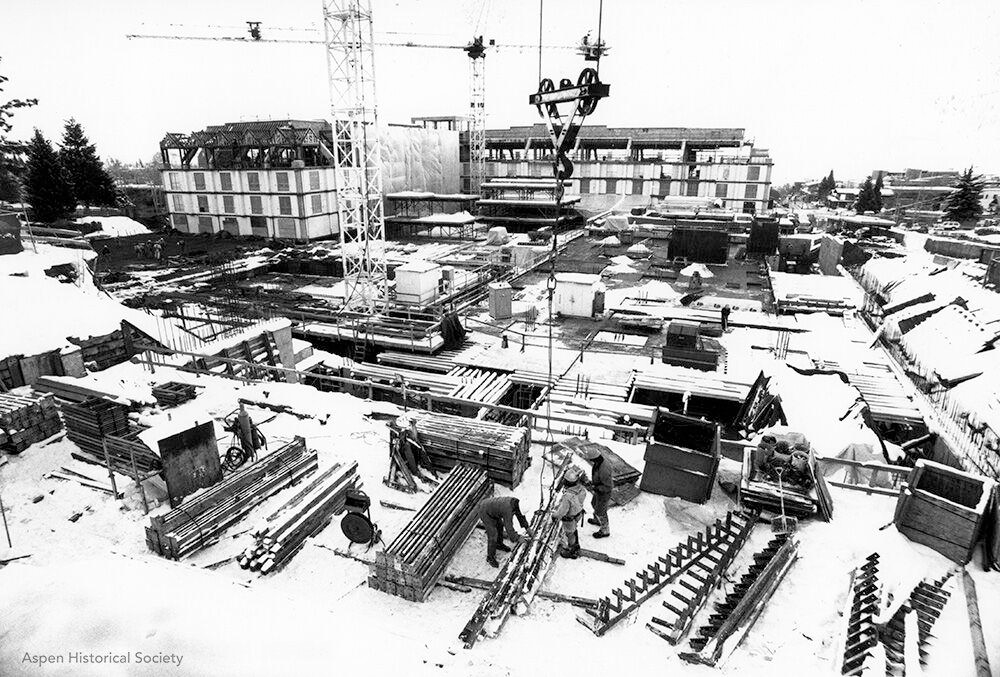

Snowmass and condo bondage

When the Snowmass ski resort was developed in 1967-68, it ushered in what Rothman termed “group think” and “a purely capitalistic economic model that ushered in the era of the condominium.” He added: “The very construction of condominiums diminished the distinctions between neonative and local. The social reconfiguration of the community matched its physical changes, depriving the older Aspen of powerful community leadership at the moment it needed it most.”

“One could buy a condominium,” observed Clifford, “use it several times a year, rent it short term for the rest of the year, apply the rental income to the purchase price, and write off most expenses courtesy of the IRS while the condo appreciated rapidly in value.” The era of the traditional family lodge was ending.

Aspen now experienced a phenomenal resort boom in which wealth became the hallmark of a high-altitude playground that harked back to the opulence of the silver barons. With the boom came the lucrative potential for growth and development that pitted factions against one another in a passionate struggle to define Aspen and capitalize on its resources. Rather than guarding only against external economic forces, Aspen had to confront internal agents of self-interest in an internecine struggle that pitted idealism against economics and slow-growthers against full-steam-ahead capitalists.

“The locals liked the town the way it was,” Clifford wrote in 1970, “a natural fortress of light and air and green and good smells. The dudes saw that sweet fortress as a bonanza and set about to mine its riches.”

“Between 1960 and 1965,” reported Rothman, “Aspen’s population rose by more than 40%, most people coming for the combination of ambiance and skiing. Included in this group were journalist Hunter S. Thompson and his wife, Sandy. Of all groups, these ‘newest-comers’ were the least enthusiastic about the increasingly corporate structure of the ski company and about the very growth of which they were part. They embraced a mythic Aspen, one that probably never existed, but they were sure that their efforts to save the community were right. They also saw protest about change as an entry into local society, a way to prove their right to local, or at least to neonative, status, paradoxically by closing the doors behind them.”

Aspen goes all aglitter

When 20th Century Fox bought the Aspen Skiing Co. in 1978, ending the era of local ownership, Aspen skiing became fully commoditized. Aspen’s fault lines widened as the city proceeded toward a vague and troubled destiny in which everyone was complicit. “We are all industrial tourists,” Rothman wrote. “Physically, we can take only pictures and leave only footprints. Psychically, socially, culturally, economically and environmentally, we inexorably change all we touch.”

Today, Aspen’s liberal fringe temperament has lost some of its formative fervor as escalated property values have pushed much of the local workforce downvalley and diffused the political influences of those who had been Aspen’s radical advocates. The downvalley exodus was, in part, an unintentional result of growth restrictions legislated to control the sprawl that had threatened Aspen’s small-town authenticity. Rapid gentrification alienated the more humble elements of the upper valley’s once-divergent population, leaving large neighborhoods mostly vacant during offseasons, when second-home owners take up residences elsewhere.

Aspen’s hallowed Shangri-La attracted the super-rich like bees to honey and, despite aggressive subsidized-housing measures, moved the workforce out. Traffic jams clogged the streets and highways as private jets clogged the skies. Contention over political and land-use issues fueled perpetual vitriolic debate as conspicuous consumption and revelry redefined the Aspen image.

In 1976, Anderson, Walter Paepcke’s successor as board chair at the Aspen Institute, warned, “The popular image of a fun-oriented, anything-goes town may not be consistent with an organization which is trying to deal with major problems in a serious manner. … Imagine trying to run a major university in downtown Las Vegas.”

By the late 1970s, the kulturstaat that Paepcke had envisioned found purity only in the cloistered sanctuary of the Aspen Meadows campus, the so-called “Circle of Serenity.” Even that bastion was under siege when, in 1980, the Aspen Institute, under Anderson’s leadership, spurned Aspen by selling its Meadows properties to local developer Hans Cantrup for $6 million. This led to a succession of developers as Cantrup lost his holdings through foreclosure to John Roberts, who in turn lost the property through another foreclosure, in 1984, to developer Mohammed Hadid and moneyman Sheik Al Ibrahim, brother-in-law of Saudi Arabia’s King Fahd.

The institute kept a 90-year lease, but a divorce was imminent as the institute and Aspen suffered seemingly irreconcilable differences in a dramatic community rift when the city thwarted the institute’s rezoning plans to develop a large hotel. After protracted dialogue and pained diplomacy, the divorce was finally reconciled in 1992, when the Aspen Meadows Consortium, a broad-based group of community-minded Aspenites, reinstated the institute’s ownership for a resale price of $10 (that’s right — $10!), constituting a generous donation from Al Ibrahim that reassured the institute’s place in Aspen’s cultural community.

John Sarpa, today an independent developer and community-minded businessman, came to Aspen in 1984 to navigate Aspen’s land-use labyrinth with Hadid and Al Ibrahim. Sarpa was instrumental in hammering out the hard-won resolution: “I was honored to be a co-chair of the Aspen Meadows Consortium, as we were able to find that elusive balance of private, local nonprofit and community interests for the long-term cultural benefit of Aspen.”

Aspen and the institute eventually made peace, but only when both parties realized the value of the other and made amends to live peaceably, if somewhat apart. But the split with Paepcke’s ideals was never rejoined. The institute dropped “for Humanistic Studies” from its title, embracing ambitious “thought leading to action” policy-oriented programs that have become global in scope.

James Sloan Allen wrote that the split between town and gown was only one more schism in an overall abandonment of Paepcke’s original humanistic idealism. “Aspen and the institute were swept up in historic currents that brought the transition from industrial to postindustrial society, from a self-denying to a self-centered character type, and from modernist to postmodernist culture,” wrote Allen. “The history of Aspen is thus the history of American culture at the mid-century and after,” when Aspen came to define what Allen termed “the culture of narcissism.”

Perhaps no one personified narcissism in Aspen more fully than a New York developer named Donald Trump, who descended upon Aspen in 1984 to bid on another of Roberts’ foreclosures. During one of Trump’s ski trips here in 1989 with then-wife Ivana, an alleged affair with a woman who would become Trump’s second wife, 26-year-old model Marla Maples, caused a stir outside Bonnie’s Restaurant on Aspen Mountain when Ivana confronted the paramours in a public display of contretemps.

Tawdry scandals aside, the fracturing of the Aspen community accelerated in a whirlwind of real estate excitements that engendered land-use controversies, a prominent one being the development of a five-star Ritz Carlton hotel (today’s St. Regis), which was completed in 1992.

Despite the soul-aching infighting, Aspen’s most unifying commonality has long been its enduring and inspiring physical setting. Today, an echo of Paepcke’s Aspen Idea — a place that nurtures body, mind and spirit — beckons to close the gap between divergent worldviews in a setting everyone can agree is an aesthetic ideal. Aspenites may not agree on politics and land use, but most agree that the Elk Mountains are stunningly beautiful. However, mutual respect for the mountains does not presuppose agreement on how to live in them. Thus, a host of ongoing upheavals have conspired to overwhelm the essence of Aspen’s shared mountain vibe. Corporeal desires and distractions have come to hold sway over loftier goals and sentiments as, for many, the “body” of the Aspen Idea has taken prominence over “mind” and “spirit.”

Profitability through tourism — what Paepcke had advocated in moderation — became the driving force for the burgeoning resort, where a profligate playground frivolity quickly overshadowed scholarly and artistic pursuits with spectacles such as the X Games, Gay Ski Week, Food & Wine, snow polo and other activities that cater to mass entertainments. In a partying atmosphere of contagious diversions, the triad at the heart of the Aspen Idea has wobbled out of balance. Robert Maynard Hutchins long ago moralized on this impasse of values: “I can never get over the notion that having fun is a form of indolence.”

The spell that had hidden Brigadoon in the mists of time was broken. Paepcke’s cloistered ideal was overrun by commercialism and the objectification of Aspen. The city retains the rich cultural vestiges of Paepcke’s dream — music, art and philosophy — for those who can afford the cover charge. Idealism was doomed. Utopia was a field of dreams. Machiavelli was put in charge of the venue, as Mortimer Adler had reckoned long before.

The “supergentrification” of Aspen

Today, the struggle for community ensues as diverse constituencies attempt to shape and mold Aspen in their own image. This ongoing battle of influences makes for a thriving political, social and cultural exchange. The debate, however, is often divisive as competing community factions vie for a share of paradise. Aspen’s volatile, argumentative soul-searching evinces an energetic fervor in debating the contrasting values that divide Aspenites with a hotly articulated sense of ownership that is especially active during times of intense change. And in Aspen, change is the only constant.

Consider lift-ticket prices, which have plotted an irreversible upward trend since the “Boat Tow” cost skiers a dime per ride. This 2023-24 ski season, SkiCo is charging $244 for a single-day lift ticket, which is still surprisingly competitive with Vail Resorts’ single-day window price of $299. Another constant, of course, is the steep climb of Aspen real estate prices into the nosebleed altitudes.

In her 2021 book, “Aspen and the American Dream: How One Town Manages Inequality in the Era of Supergentrification,” sociologist Jenny Stuber pinpoints Aspen’s social-engineering challenge through the guiding of development as described by a city planning goal: “a process of place-making that involves the careful orchestration of diverse class interests within local politics and the community, with the overarching goal of maintaining Aspen’s value and preserving its authentic small-town character.”

Many would say that Aspen’s small-town character is on life-support, a casualty of the supergentrification that has made Aspen a social and economic anomaly: “The conventional wisdom,” writes Stuber, “is that a place like Aspen should not exist. That is, a place should not exist where the median income is $73,000 per year, but the median home price is over $10 million. … These dynamics should make it impossible for a community to exist where the incomes earned by local residents are fundamentally at odds with the housing prices, and where working locals still exert considerable influence on how the town operates.”

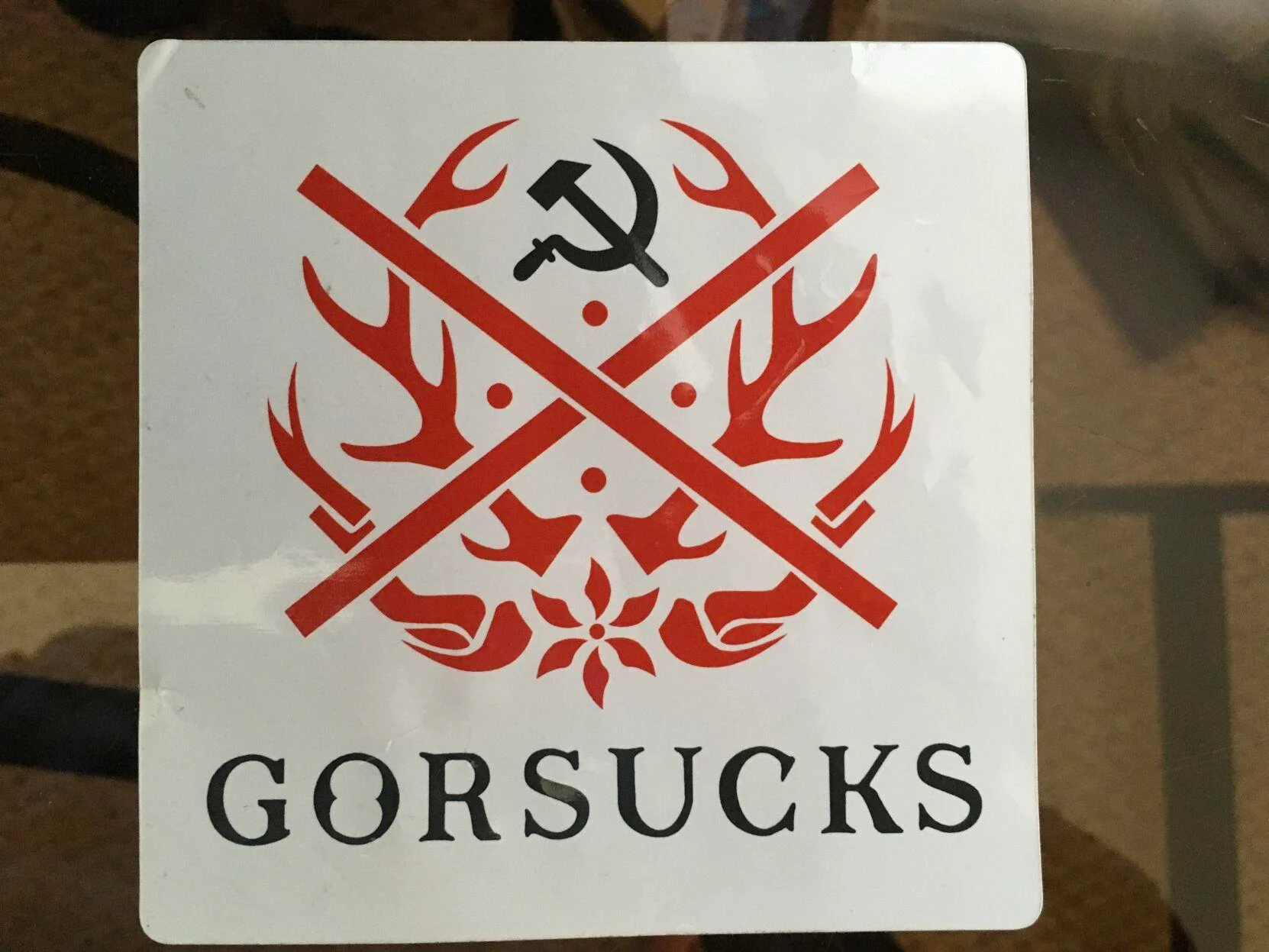

Working-class Aspenites have struggled to keep up against long odds. When ski patrollers organized and went on strike for higher wages in the ’70s and ’80s, a picket sign at the newly installed Silver Queen gondola in 1986 read: “SkiCo got the Silver Queen. We got the shaft.” Other beachhead controversies have kept passions inflamed: the four-laning of Highway 82, the Ritz-Carlton and Little Nell hotels, the private fou-fou Caribou Club, a proposed ban on fur coats, Prince Bandar’s 55,000-square-foot monster home, airport expansions, the Lift One Gorsuch kerfuffle, the outrageous displays such as Champagne-spraying debauches at Cloud Nine, and the opulent excess of Aspen X.

Stuber accurately analyzes the perpetual growth mandate that has driven Aspen for more than five decades: “A pro-growth agenda is pushed by economic elites and government officials who seek to maximize the exchange value of a place — its economic value in terms of how much it can be rented or sold for. … Yet local residents are typically no match for the growth machine, which benefits from the deep pockets and continuous, institutionalized support of local political regimes.”

Stuber writes that Aspen currently caters to those “with upscale global tastes.” What makes the place attractive, she infers, is a tantalizing blend of historic, homespun Colorado mountain chic and urbane corporeal and cultural pleasures. The community, she opines, is “co-opted by economic elites and a ‘butler class’ of professionals — lawyers, accountants, politicians and more … who help them achieve their goals.” These goals are clearly visible in conspicuous consumption and conspicuous waste — two societal sins in Thorstein Veblen’s lampoon, “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” in which Aspen could be a case study.

“Aspen is a rare town,” said Ann Bond, a consulting curator from the State Historical Society, “in that it has a solid history of boom and bust, as well as a wide range of industrial and commercial development through its history. However, the defining attribute of Aspen in the last 40 years has been its role as one of few internationally famed resort/living communities for the extremely wealthy of the entire world. This quality of the town is so pervasive that it is visible always.”

A local columnist emoted several weeks ago in the Aspen Daily News that it is no longer a true ski town: “Aspen is a corporate town replete with middle managers. Aspen is a town where the hyper-wealthy can go mental on hedonism. Aspen is a town where absentee landlords can mine money while giving absolutely nothing back. Aspen is a shopping town, an upscale mall. Aspen is a bedroom community where nobody lives in the bedrooms.”

“The lessons of the Western past appear in complex layers in the Roaring Fork Valley,” observed University of Colorado Boulder history professor and author Patricia Limerick. “From the impermanence of the traditional extractive economy to the benefits and costs of the contemporary tourist economy, understanding Aspen means understanding crucial regional issues.”

A devastating future, or a model for excellence?

In a 1999 speech to the Aspen Institute Society of Fellows, Aspen Mayor John Bennett, who served from 1991 to 1999, pointed out emergent regional concerns. In 1991, he said, the Roaring Fork region had a population of 48,000. By 1998, that number had grown to about 60,000. “The new people moving here in the next decade will make an extra 120,000 automobile trips per day in our valley,” Bennett predicted. “Our Roaring Fork region’s underlying zoning today will allow a total build-out of 300,000 people. The impact of such growth on our environment and quality of life would be devastating.”

Bennett warned that arguing over opposing values has threatened a breakdown of civility. “We are in danger of succumbing to a politics of division and anger, an anger that is reflected in letters to the editor in any given week,” he said. “Indeed, the shrillness of uncivil dialog appears to grow almost monthly, with big-city accusations of fraud, patronage, lying and general malfeasance on the part of anyone in public office. For some of our citizens, engaging in an honest and open dialogue with neighbors in a small town has been replaced by sitting at home, alone with a word processor, and firing off ugly emails to the local newspapers. Aspen has become a political battleground.”

This ugly tone, said Bennett, threatens to tarnish “a city which has celebrated the life of the mind, a place of the arts in the human experience, the politics of class, the fine-tuning of the body through mountain sports, the values of rural living, and a vibrant and contagious youthfulness.”

Countering this note of despair, Bennett offered a way out: “Our role is to provide a model for excellence, not merely for being a wealthy town in a beautiful place, but a model of civilization in a small community. We can offer the world a model of a community consciously founded on a vision and a dream. We owe it to our founders — but far more important, we owe it to ourselves — to live up to that dream.”

This concludes our four-part look at the historic struggle to define community in Aspen. The “In search of community series” from Paul Andersen and Aspen Journalism will continue in the weeks to come. Catch up on each installment at http://aspenjournalism.org.