For now, the CuMo Exploration Project is just that: Exploring, without full-scale mining operations.

The test project proposed by the Idaho Copper Corporation would be outside Idaho City, a town home to less than 700 people about 30 miles northeast of Boise.

A 2020 analysis found the project area could have deposits of silver and critical minerals used in renewable energy, national defense and last-ditch efforts to expand drinking water availability.

Environmental advocates worry the test project could taint headwaters that feed into the Boise River, and they are skeptical that regulators have fully identified possible impacts.

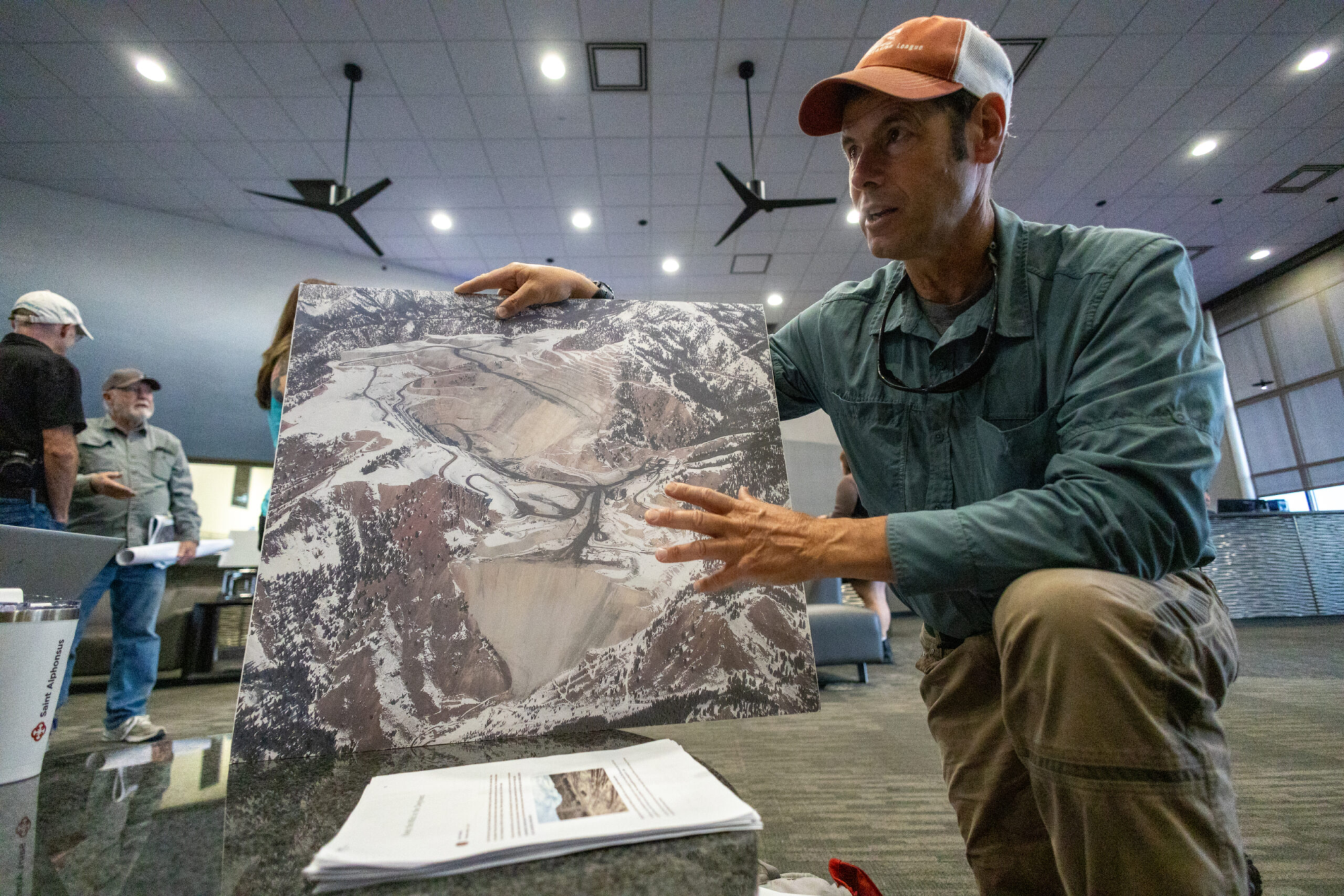

“Ultimately, responsible mining means that some places are too special to mine. And we think that the CuMo project cannot be developed — explored or developed — in a way that’s going to be adequately protective of the Boise River,” Idaho Conservation League Public Lands and Wildlife Director John Robison told the Idaho Capital Sun in an interview. “Given the track record of mining, and of this scale and type of mining, it seems impossible to do both that and protect the Boise River for everyone who relies on it.”

But Idaho Copper Corporation CEO and COO Andrew Brodkey says the test project wouldn’t harm the Boise River. And he stresses that a possible, actual mine would be years away — depending on the economic prospects — and involve more environmental analysis beforehand.

“We’re not even close to making a decision whether a mine should be put in,” Brodkey told the Sun in an interview. “All we’re trying to do is develop information that will give us the basis to make that sort of a determination.”

What is the CuMo Exploration Project?

The 2023 CuMo Exploration Project is a four-year mining exploration proposal, about 14 miles north of Idaho City.

The planned project area is 2,917 acres. The company’s proposed test drill project would affect only 72 acres, Brodkey said.

The test would feature 122 drill pads and construction of 8.9 miles of temporary roads. Within two years after the project is completed, all drill pads and temporary roads created would be removed and restored.

Afterward, the company plans to close off and cap up to 250 drill holes, “so that there can’t be any contamination,” Brodkey said.

The Idaho Copper Corporation is advancing the CuMo Project “towards feasibility and its goal is to establish itself as one of the world’s largest and lowest-cost primary producers of molybdenum,” the company said on its website.

The company “is studying all factors” and “is committed to exhaustive adherence to modern mining practices, stewardship of all natural resources, reclamation of the preexisting historic mining damage, and meaningful community engagement,” its website says.

A decision on whether the project would turn into a full mine would likely be in at least four or five years, Brodkey said. And it’d require a more comprehensive environmental impact statement, detailing possible environmental effects, he said.

After public comments closed on an environmental assessment on the proposal, the U.S. Forest Service is reviewing whether the test project can proceed.

Where is the CuMo project in the review process?

The U.S. Forest Service is responding to public comments and building the final environmental analysis and technical reports, Boise National Forest’s Idaho City District Ranger Joshua Newman told the Sun in an email. A draft decision would be developed and published after, he said.

The next types of project reports set for public release vary based on whether the Forest Service identifies “significant” impacts, after reviewing public comments, Newman said. The documents would include a final environmental analysis and draft decision, he said.

That would start a 45-day objection window. If uncontested, the agency would issue a final decision document after, he said. But objections could trigger another 45-day objection review period, Newman said.

The Forest Service hopes to publish its environmental analysis within the next month, Newman told the Sun. But that depends on the agency’s capacity while it battles wildfires.

What are the environmental concerns?

Robison said environmental groups have pushed the U.S. Forest Service to evaluate project impacts that the agency initially didn’t do, like establishing baselines for water quality and the rare Sacagwea’s bitterroot in the project area.

“Even if it’s a pretty low bar, it’s not being carried out as it should,” Robison said. “That’s why we want to bring more scrutiny. What else have you guys missed on this?”

The Forest Service’s reports on the proposed project used data from water sampling, spanning a decade, and baselines for Sacagawea’s bitterroot, Newman said.

But Robison says the legal standards guiding Forest Service reviews aren’t adequate.

Brodkey said the project wouldn’t affect the Boise River or any watersheds, saying the Idaho Copper Corporation’s plans are “very much circumscribed” by environmental law and regulations.

“The science, I believe very strongly, will bear us out,” Brodkey said. “The hydrology, the plant species, the animal species — everything that we will be looking at will be done and has been done in a very comprehensive manner,” he told the Sun. “So that the environmental effects of this project are not going to be items that people should be worrying about.”

Amid climate change and water shortages, CuMo part of push for domestic mining

Renewable energy systems rely on copper — one mineral that may have deposits in the project area — more than traditional energy systems. And copper is in higher demand from the growing electric vehicle market, according to the International Copper Association.

“Copper is an incredibly important critical mineral for the energy transition and the avoidance of global warming,” Brodkey said.

Meanwhile, the U.S. imports much of its copper from overseas, according to the National Mining Association. But America has the minerals, Brodkey said, and advancements may let the U.S. produce more copper domestically.

Another metal the company seeks at the site, called molybdenum, makes steel more resistant to corrosion. It has applications in desalination plants — which turn salty sea water into potable drinking water, like in South America.

“I think ultimately that’s going to end up happening here in North America as well, as we start to lose our ability to rely on existing surface and ground water sources,” Brodkey said.

He said the U.S. Department of Defense is interested in rhenium, another metal potentially in the project area.

The mine is part of a broader push for so-called energy security or resource nationalism — that involves ramping up domestic U.S. production of resources typically imported from other countries.

“If you ask people on the street where would they rather have their material source from — from a place where it’s going to cause problems and deaths, even though it’s in another country. Versus here, where we have to comply with some pretty stringent laws and (regulations), I think that they would tell you that they would rather know that the materials that they’re using are coming from people that are responsible,” Brodkey said.

The Idaho Conservation League acknowledges the need for mining and minerals, especially to mitigate climate changes’ impacts, and is seeking ways to “responsibly develop our mineral resources,” Robison told the Sun.

But, he called for communities to have a bigger role in mining project plans to ensure communities benefit and that their quality of life, and water quality, doesn’t diminish.

“The rule set that we follow to date has left Idaho with a horrible track record, or has left Idaho with far too many examples of contaminated water and affected communities,” Robison said.

In central Idaho, the Thompson Creek mine might restart operations, Boise State Public Radio reported. Robison says it “makes far more sense” to get the minerals there.