Days before Utah lawmakers are set to convene, dozens of researchers are calling on them to take bold action and save the Great Salt Lake before it withers away.

An emergency briefing released Thursday warns of “unprecedented” danger to Utah’s public health, environment and economy if the lake does not receive a “dramatic” influx of water by 2024. The lake has already hit record-low elevations for two years in a row, exposing 60% of its lakebed which continues to dry into a toxic source of dust pollution. Excessive water use in the Great Salt Lake’s basin means the lake is set to disappear in the next five years, the report warns.

“The decisions we make in the coming few months will affect our community and ecosystems across the hemisphere,” said Ben Abbott, a professor of Aquatic Ecology at Brigham Young University and lead author of the briefing, in a news release.

Scientists and conservationists with Westminster College, Friends of Great Salt Lake, the University of Alberta, Utah State University, Wasatch High School, Utah Valley University, Great Salt Lake Audubon and more co-authored the study.

The Utah Legislature took some of its biggest conservation measures to date last session in an effort to save the Great Salt Lake. They took a helicopter tour of its massive exposed lakebed and approved a $40 million trust to secure water rights and improve habitat for the lake. They funneled millions toward mandatory secondary water metering. They revised the state’s pioneer-era water laws to allow farmers to lease their water rights and use them to benefit environmental interests like the Great Salt Lake.

In recent months, Gov. Spencer Cox closed the lake’s watershed to new water rights. His latest budget proposal calls for $132.9 million to help the lake specifically, along with another $217.9 million for statewide water conservation.

But lake researchers and advocates say it’s not enough.

The briefing calls on the governor to take emergency action to save the Great Salt Lake, including a requirement that 2.5 million acre-feet reach it each year until waters rise to a sustainable elevation.

Lawmakers also need to set aside a significant amount of money to ensure all the recent policies they’ve adopted lead to water making it all the way to the lake, according to the report. The agriculture industry has so far expressed reluctance about fallowing fields and leasing water, even as state leaders constantly tout those measures as winning solutions for the Great Salt Lake.

And, the briefing adds, conservation efforts need to be far more aggressive by every water user in the Great Salt Lake’s watershed. Attempts to date have delivered just a drop of what it needs to recover.

“We are in an all-hands-on-deck emergency,” the report warns, “and we need farmers, counties, cities, businesses, churches, universities, and other organizations to do everything in their power to reduce outdoor water use.”

State lawmakers must think bigger, the report notes, and recognize the lake’s right to exist.

“This respectful approach to God’s creation,” the report says, “is in line with the religious and cultural teachings of the Indigenous and immigrant peoples of Utah.”

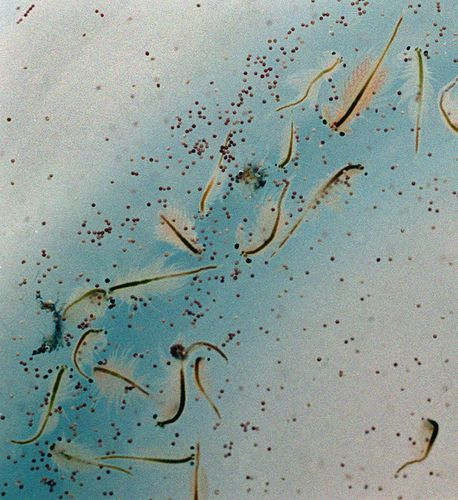

Meanwhile, the Great Salt Lake’s collapse has begun. High salinity levels have all but wiped out brine flies, which support millions of migrating birds. Microbialite colonies that serve as the foundation of the lake’s food web have surfaced and died. The lake’s multimillion-dollar mineral extraction industries can’t reach the brine they need, marinas are dry and the lucrative aquaculture industry could go bust next year if rising salinity wipes out the lake’s brine shrimp.

The report estimates the lake contributes $1.8 billion to Utah’s economy and supports 8,800 jobs.

“In the face of this [crisis], we need our state leadership to say, ‘Not on my watch,’” said Lynn de Freitas, executive director of Friends of Great Salt Lake, “and do whatever it takes to pull the lake back from the edge.”

Talk of pipelines to the Pacific, new dams and cloud seeding imply state leadership may not realize how imminent the catastrophe looms, or how dire its consequences will be.

“Conservation is the only way to provide adequate water in time to save Great Salt Lake,” the report says.

“Conservation is also the most cost effective and resilient response.”

And while climate change and the West’s “megadrought” are creating water shortages and environmental stress across the region, human consumption is mostly to blame for the Great Salt Lake’s desiccation. The lake has lost more than 1 million acre-feet each year since 2020, according to the report, which is “much more” than models predicted.

The lake currently sits about 10 feet lower than its minimum healthy elevation, the report notes, which represents a shortage of 6.9 million acre-feet. And while much attention is paid to the lake’s shrinking shoreline, the briefing warns of an impending groundwater crisis as well in the Great Salt Lake Basin — signs of which are already beginning to show.

Evidence of the lake’s contribution to dangerous dust is popping up across the West as well. Sediment from the Great Salt Lake has been observed from southern Utah to Wyoming, according to the report, and contributes to accelerating snowmelt along with worsening air quality. The lake’s dust has concerning materials, including arsenic. But fine particulate matter blowing from the lake will be disastrous for the people living along the Wasatch Front regardless of what’s inside it.

“The Great Salt Lake can be either an extraordinarily beautiful jewel of nature or a serious hazard to human health,” said Paul Alan Cox with Brain Chemistry Labs in Jackson Hole. “The choice is ours.”

Along with its recommendations, the emergency briefing has a list of things Utahns should not count on to save the Great Salt Lake. It calls cloud seeding “experimental and unproven.” Building pipelines and more dams doesn’t make sense, the report warns, as Utah is having trouble keeping its existing reservoirs full.

The report further laments efforts underway to sacrifice the lake’s north arm by using a railroad causeway to cut it off from freshwater sources. The north arm serves as critical nesting habitat for pelicans, provides brine for industry and is a vast pending source of lakebed dust.

And even though the state has seen some promising storms this winter, Utahns shouldn’t wait for the rain to save the Great Salt Lake, the briefing warns.

“Recent snowfall puts Utah well above average for the current water year, but we’re still very far behind,” said Rob Sowby, professor of Civil and Construction Engineering at BYU. “We’ve had precipitation; now we need policy, priorities, and people to make the most of it.”

This article is published through The Great Salt Lake Collaborative: A Solutions Journalism Initiative, a partnership of news, education and media organizations that aims to inform readers about the Great Salt Lake.