Nearly 20 years of work by conservationists, ranchers and outdoor enthusiasts to prevent oil and gas drilling in the Thompson Divide area west of Carbondale bore fruit Wednesday when the Biden administration withdrew 221,898 acres from potential leasing.

Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland signed Public Land Order 7939 that removed a vast swath of public land in Pitkin, Garfield and Gunnison counties from mining, mineral and geothermal leasing for a 20-year period.

“It’s a one-in-a-generation win for the community,” said Francis Sanzaro, a spokesman for Carbondale-based environmental group Wilderness Workshop.

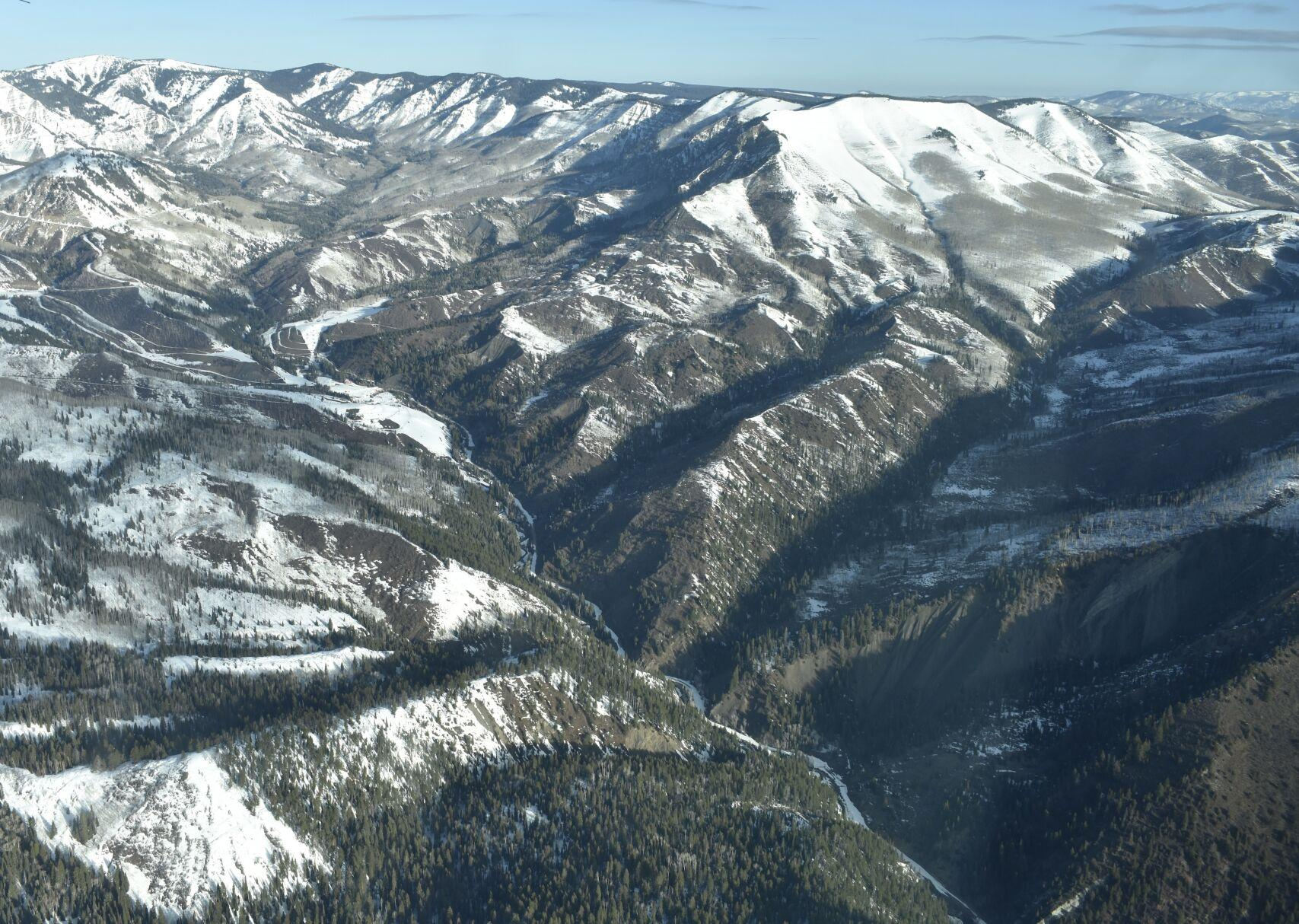

The order affects lands stretching from south of Sunlight Mountain Resort to the Mt. Emmons area outside of Crested Butte. The withdrawal includes 67,040 acres of the White River National Forest in Pitkin County and another 11,432 acres in Garfield County. Those are lands people from the Roaring Fork Valley are most familiar with because they are located west of Carbondale.

But during the debate over the fate of the lands, the area targeted to be protected grew over the years to include 122,000 acres in Gunnison County. About 15,000 acres of land managed by the BLM was included in the withdrawal as well as nearly 9,000 acres of reserved federal mineral interests.

While in Colorado to establish the Camp Hale monument in October 2022, President Biden announced he had ordered a study of the Thompson Divide withdrawal. That triggered an environmental assessment that concluded with Haaland’s decision on Wednesday.

“The Thompson Divide area is a treasured landscape, valued for its wildlife habitat, clean air and water, and abundant recreation, ecological and scenic values,” Haaland said in a prepared statement. “The Biden-Harris administration is committed to ensuring that special places like these are protected for future generations.”

The decision drew praise from conservation groups. Wilderness Workshop hailed the decision as the result of a “strong community collaboration.”

“This is a long, long time coming. Wilderness Workshop and local communities have been working for over a decade to safeguard this incredible landscape,” said Will Roush, the nonprofit’s executive director.

Wilderness Workshop helped create the Thompson Divide Coalition, a group focused solely on protecting that area. The two groups and partners successfully convinced federal officials during the Obama administration to cancel 25 leases in the Thompson Divide area in 2016. The White River National Forest also determined it wouldn’t make new leases available in the area, but the protections weren’t necessarily permanent. That’s why the effort switched focus to getting the 20-year withdrawal approved.

The withdrawal is “stronger, more concrete and bigger,” said Peter Hart, an attorney with Wilderness Workshop. “The Forest Service decision was smaller in geographic scope — only applying to portions of Thompson Divide in the White River National Forest. (This action) is stronger and more concrete because this is a decision of the Secretary of Interior rather than the local forest supervisor, and it will last for 20 years. The forest service supervisor’s decision could last for 20 years, or until another forest supervisor changed it — it doesn’t have a term certain.”

Ranchers wanted to make sure grazing lands and water sources were protected. Conservationists wanted to prevent development of roadless areas and wildlife habitat. Outdoor enthusiasts wanted mountain biking, hiking, climbing and hunting opportunities left unscathed.

Bill Fales of Cold Mountain Ranch has grazing rights in Thompson Divide. He’s been involved in efforts to protect the area since leases started getting gobbled up in the mid-2000s. He said Wednesday he was always confident that the area could be protected.

“But we were so naive. We had no idea of what it would entail to get here,” he said. “We just thought, ‘Oh, we’ll just call up and get this done.’ And it’s more complicated than that.”

The reason for his confidence was the broad-based community support, including the county governments of Pitkin, Gunnison, and, most of the time, Garfield.

“It seemed like everyone was pulling for it, so why wouldn’t it go?” Fales said.

Wilderness Workshop and partners put a lot of effort into studies that showed why the area should be preserved. One study showed about 110,600 acres, or 49% of the Thompson Divide area, was one of the most important ecosystems in Colorado. It provides important migration corridors for lynx, moose, elk, deer, bears and mountain lions. In addition, 34,000 acres received a top score for ecological connectivity because of unfragmented habitat.

Energy industry officials contended that history shows oil and gas leasing could co-exist with environmental protection.

“Efforts to shut down oil and natural gas in the Thompson Divide area going back at least to the 2000s have been centered around a mistaken belief that oil and natural gas production is incompatible with other multiple users,” said Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Denver-based Western Energy Alliance. “There’s been oil and natural gas activity in the area since the late 1940s. The fact that scenic values have been preserved since the 1940s and the land is still considered pristine undermines the arguments of those who strive against balance and wish for absolutely no oil and natural gas activity.”

Sgamma also questioned if there was a legitimate assessment of the withdrawal proposal. “The fact that this was rushed through so quickly after the public comment period indicates this withdrawal was predetermined from the outset,” she said.

The federal Environmental Assessment on the withdrawal said the action would prevent the development of up to four well pads that would serve seven to eight wells with no major restrictions. The study said it was possible that up to seven pads serving 12 to 13 wells could be developed in the broad area.

The study also said there are 22 active oil and gas leases within the withdrawal area. Those will remain active and unaffected by the withdrawal. There are another 63,582 acres with a high potential for locating oil and gas.

Sgamma said there are companies such as Gunnison Energy that are dedicated to exploration and production in Colorado’s Western Slope. Gunnison Energy submitted comments during the environmental assessment that said it has invested significant funds into infrastructure necessary for exploring and producing in the Thompson Divide area. In addition, it believes the study on oil and gas potential was flawed and underestimated the sources. It asked the interior department to reduce the acres affected by the withdrawal.

The interior department noted the withdrawal won’t affect the Wolf Creek Gas Storage Area, an underground natural gas storage field that serves the Roaring Fork Valley. Valid existing rights to drill also are left intact. The decision only pertains to federal lands, not private property.

While hailing the decision and protection for 20 years, conservation groups are still holding out hope for approval of the Colorado Outdoor Recreation and Economy Act, or CORE. If approved, it would provide permanent protection for the Thompson Divide area rather than a 20-year pause.